Nir’s Note: This post part of a series on cognitive bias co-authored with and illustrated by Lakshmi Mani. Discover other reasons you make terrible life choices like confirmation bias, hyperbolic discounting, extrinsic motivation, fundamental attribution error, hindsight bias, and peak end rule.

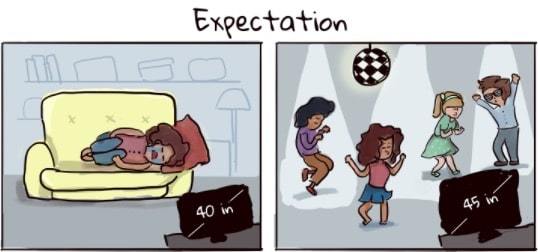

There I was, looking at an enormous wall of television screens. Each one flashed the exact same scene? —? a beautiful flower slowly blooming to reveal each petal, pistil, and stamen in exquisite super high definition detail. It was downright sexy. But now it was time to make my choice.

Would I buy the $400 television within my budget or would I splurge on the $500 deluxe model that somehow helped me understand plant biology in a new, more intimate way?

Though every cone and rod in my eyeballs begged me to buy the better one, my more sensible instinct kicked in. “Your budget is $400, remember?” Sighing, I bought the crappy model and braced for a life of media mediocrity.

But then, a strange thing happened. When I fired up the new set at home, it looked fine. Better than fine in fact. It looked great! I couldn’t figure out why I even wanted the pricier model in the first place.

Why the change of heart?

Among a host of brain biases, I fell victim to distinction bias — a tendency to over-value the effect of small quantitative differences when comparing options. In the store, I was in comparison mode, evaluating the TVs side by side; hypersensitive to the smallest differences. But at home, there was just one TV and no alternatives to compare against. It was glorious in its singularity.

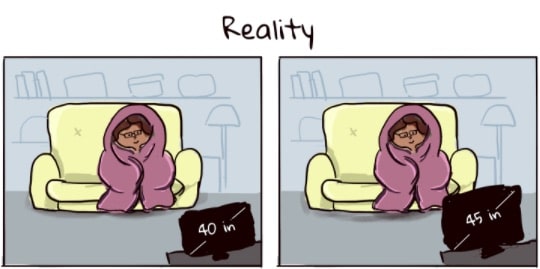

Let’s do a little experiment together. I want you to pick between two options.

Option 1: I’ll give you one Hershey Kiss worth of chocolate if you think of a time in your life when you experienced personal success.

Or…

Option 2: I’ll give you three Hershey Kisses if you think of a time in your life when you experienced personal failure.

Which would you choose?

Which would you choose?

In studies, about two-thirds of people opt for more chocolate. Clearly, more is better, right? Not always.

Despite the fact people chose freely and presumably wanted to maximize their happiness, those who opted to think of a negative memory for more chocolate were significantly less happy than those who chose a positive memory for less chocolate. And, lest you think the effect might be a result of feeling guilty for eating fattening chocolate, the researchers thought about that too. Yet, they found no significant difference between the two groups when it came to feelings about eating the candies. So what gives?

Your Brain Isn’t That Smart

Psychologists believe we are in two different modes when we compare options versus when we experience them. When making a choice, we are in comparison mode — sensitive to small differences between options, like me choosing a television. But when we live out our decisions, we are in experience mode — there are no other options to compare our experience to.

In comparison mode, we’re pretty good at deciding between qualitative differences. For example, we know that an interesting job is better than a boring one or that being able to walk to work is better than having to suffer driving in rush hour traffic.

When I asked you to pick between Option 1 or 2, you likely could have told me recalling a personal success story would feel better than recalling a failure. So why do people choose Option 2? For more chocolates of course! And that’s where things get sticky.

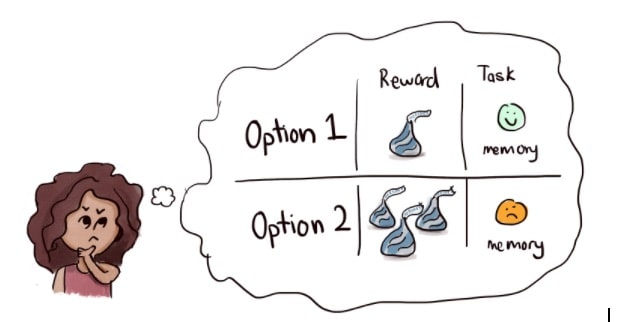

Humans are not very good at predicting how quantitative differences, those involving numbers, affect happiness. In the experiment, people assumed three Hershey Kisses worth of chocolate would bring them three times the happiness. But it didn’t.

We make the same mistake in real life all the time. We think a 1,200 square foot home will make us happier than a 1,000 square foot home. We think earning ,000 a year will make us happier than earning ,000 a year.

We often place higher emphasis on inconsequential quantitative differences and pick an option that won’t actually maximize our happiness.

How to Outsmart Your Brain

1. Don’t Compare Options Side by Side

In comparison mode, we end up spending too much time playing “spot the difference.” This is where we run into trouble and focus too much on inconsequential quantitative differences. To combat this, avoid comparing two options side by side.

What can we do instead? Evaluate each choice individually and on their own merit.

If you are buying a house, don’t compare one with another. Spend time at each house focusing only on what you like and dislike about that house to form a holistic impression of it. That includes everything from the size of the house, your commute, how close your friends live, it’s warmth and coziness all the way down to how weird the neighbours are.

Now, choose the house that registers the best overall holistic experience.

2. Know Your “Must-Haves” Before You Look

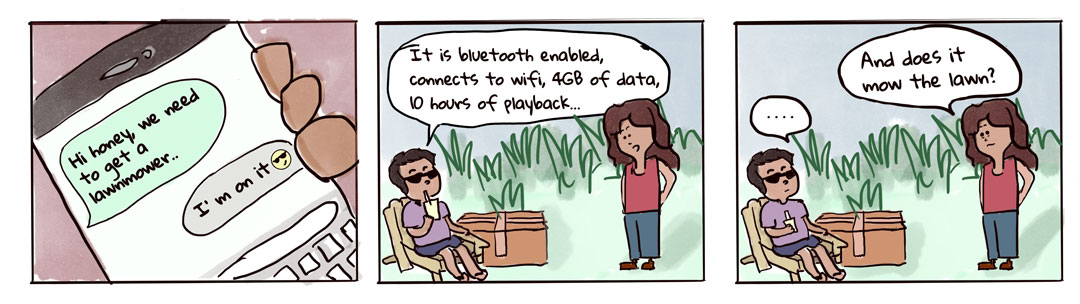

Clever marketers often use distinction bias to trick us into paying more for things we don’t actually need and won’t make us any happier!

So next time, defend yourself by writing down what really matters before you shop. Write down your must-have reasons why you’re buying the item. Then, once those conditions are met you’ll be free to pick the cheapest option that has your requirements without getting suckered into features you don’t really need.

3. Optimize for things you can’t get used to

Researchers believe that we fall victim to distinction bias when we underestimate our tendency to return to a baseline level of happiness over time — this tendency is known as “hedonic adaptation.” Despite thinking we’ll live happily ever after, a higher income or a bigger house doesn’t make us happier for very long.

As a rule of thumb, your happiness will adjust back to anything that is stable and certain like your income, the size of your house, or the quality of your TV. These things do not change day to day so you can expect your happiness level to fade.

On the other hand, infrequent or uncertain positive events, like quality time with friends or an exciting road trip, occur too sporadically to get used to. Inserting more of these hard-to-adapt-to experiences in your life will create longer lasting happiness.

When our species first evolved, picking the ripest fruit on the bush or selecting the right animal from the herd served us well. Today however, the same shortcut that helped us survive can get us into trouble. Instead of optimizing for what will make us happier in the long-term, we play “spot the difference” regarding attributes that don’t matter much. Though savvy marketers can use this bias to sell us stuff that may not make us better off, there’s no reason we have to keep falling for their tricks. After all, the trick is in our own heads. By understanding our cognitive quirks, like distinction bias, we can outsmart our own brains.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier