By Nir Eyal and Todd Snyder

Let’s play a game of “would you rather.”

Would you rather speak in front of 500 people for an hour or be stuck in an elevator with your ex?

Would you rather get a cavity drilled or be forced to take a four-hour Zumba class?

Would you rather lose your car keys before work or lose your internet connection before an online meeting?

None of these options are good, but they all have something in common: they invoke stress.

What stresses you out? How do you deal with that dreaded feeling? And did you know there’s a bullet-proof method for disarming stress?

Where Does Stress Come From?

Stress is defined as “mental or emotional strain resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances.” We’ve all felt it, but where does stress come from?

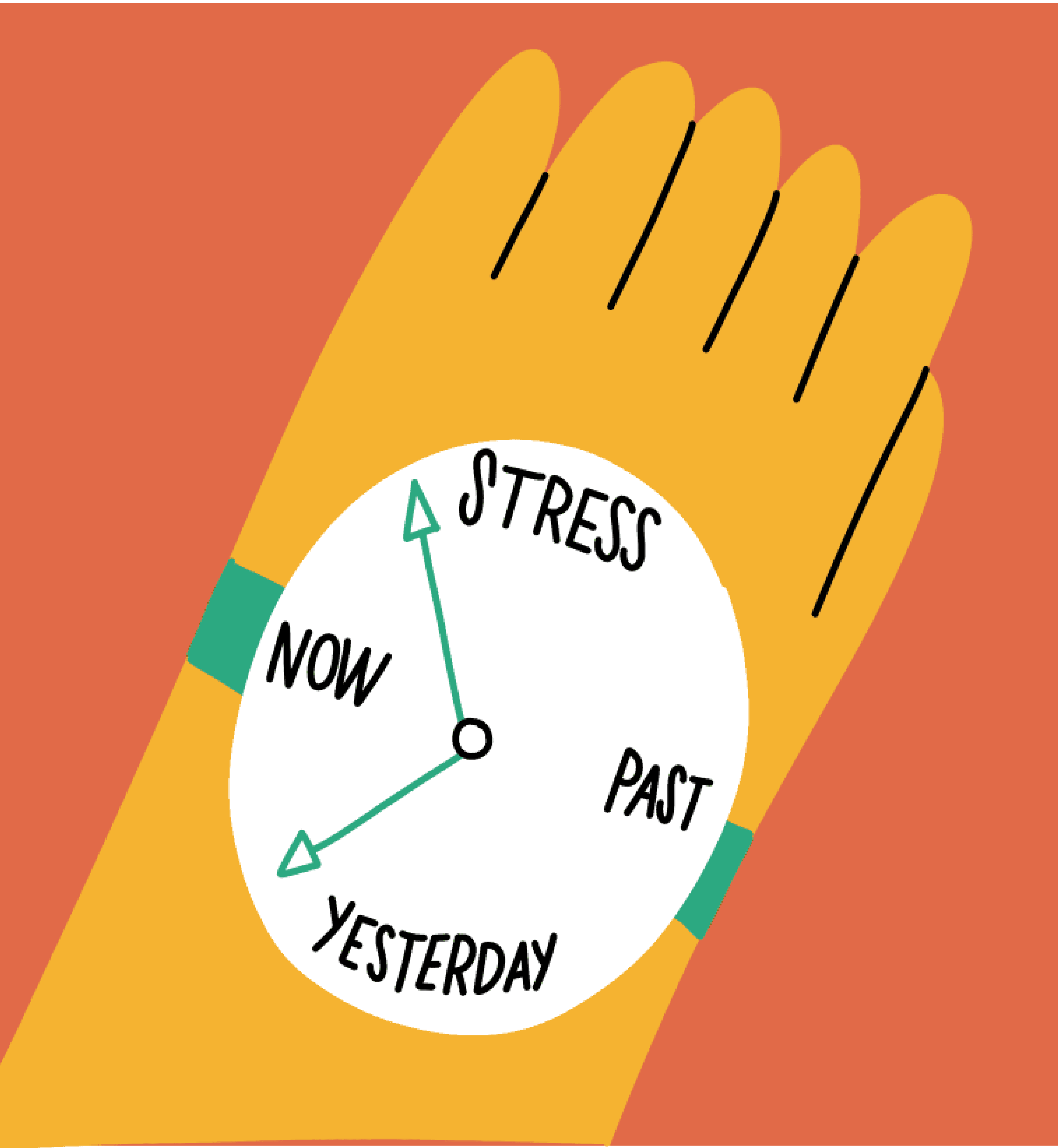

Stress comes from the future, but not in the Marty McFly way.

Humans are unique in our capacity to predict what might happen next. We rely on our amazing ability to anticipate the future better than any other animal, and this ability is a feature of our unusual intelligence.

Unlike other animals, which (as far as we know) react solely to what’s going on in their environment, humans can imagine entire realities in our heads. These alternate realities make us act in all sorts of strange ways. For instance, while zebras will run from the sound of a lion in the brush, humans will stampede at the start of a Black Friday sale, imagining the deals we’ll miss if we don’t elbow our way through.

While imagining the future motivates us to pursue what we want, it also comes with a cost. All that thinking about what might happen next is stressful.

Does that mean humans are doomed to lives of constant stress? Does our ability to imagine many futures mean we’re destined to feel constant emotional strain?

Not necessarily.

You’ve no doubt heard the story of Viktor Frankl, the inspiring psychiatrist who survived imprisonment in a Nazi concentration camp during the Holocaust. He observed firsthand the profound difference between his fellow prisoners who lost hope—and soon died—compared with those who found a purpose. Focusing on that purpose allowed them to take back some measure of psychological control. The difference was literally life and death.

What if I told you that same powerful difference in focus and mindset is impacting you right now?

You’re about to learn how to create a real-life forcefield against the stress you face every day.

Viktor Frankl knew something science would later verify: perception can mediate the effects of stress. In other words, two people faced with exactly the same stressful situation can have very different physical and emotional reactions. How does that happen? To answer that question, let’s take a look at some fascinating research about the power of feeling in control.

The Power of Control

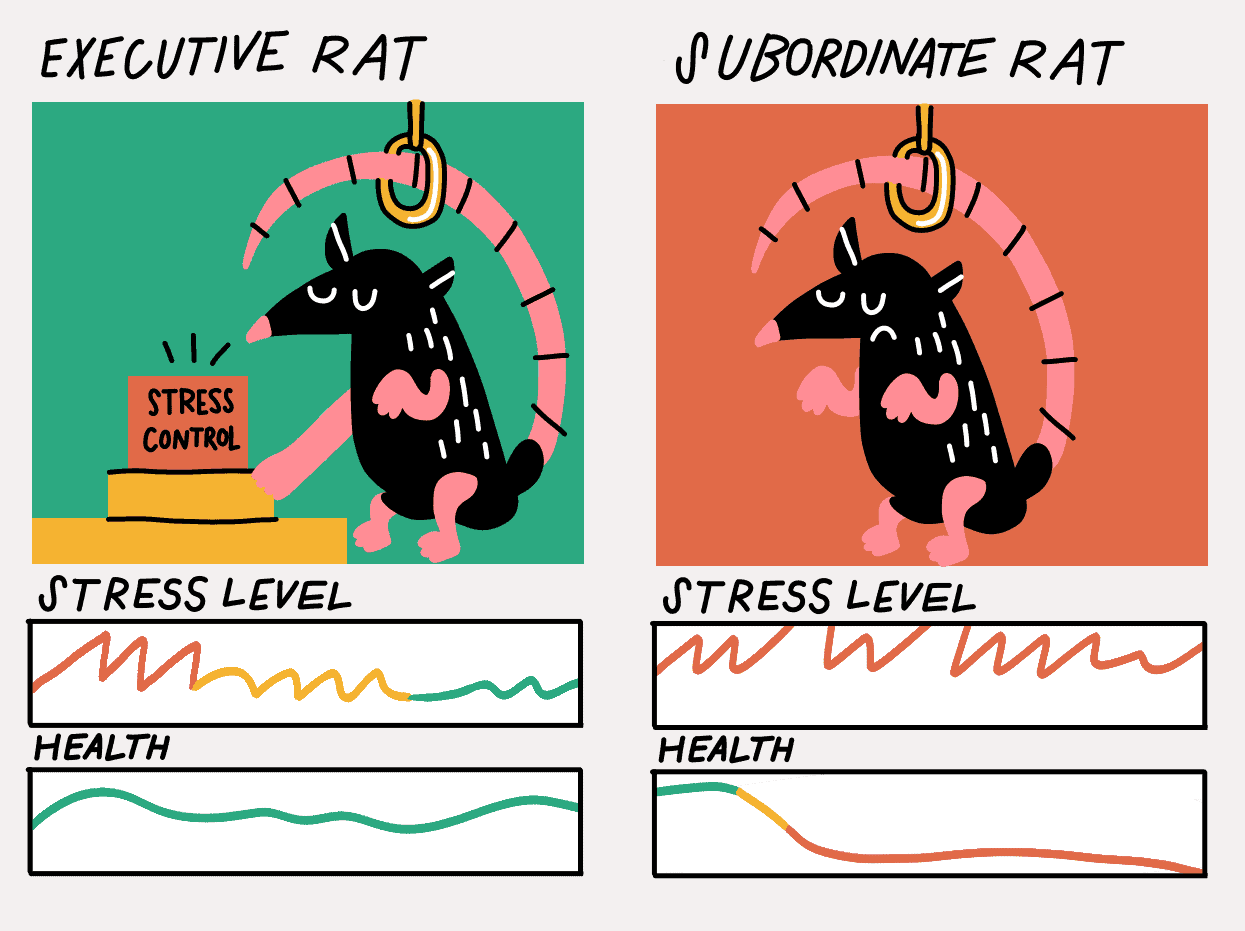

A classic study of two rats (journal article by D.L Helmreich et al) reveals an important insight about the role control plays in the experience of stress. The two rats are in separate cages connected to the same electrical circuit. The circuit administers random shocks through the metal floor of their cage. One rat has a lever in its cage that enables it to turn off the shocks while the other rat does not.

The rat with the lever in its cage is called “the executive rat,” because it has control. It has the power to turn off the electric current flowing through the cage. The rat with no control is called the “subordinate rat.”

When the experiment begins, both the executive rat and the subordinate rat show signs of stress, indicated by a sudden surge of the stress hormone, cortisol. Then, something interesting happens. The executive rat’s stress levels drop back to normal, while the subordinate rat’s stress remains high. Why? In a word, control.

The executive rat has discovered that it can turn off the stressful stimulus (the random shocks) by pressing the lever in its cage. For the executive rat, it’s as if the physiological effects of its stressful situation have been turned off completely. In contrast, the subordinate rat’s health steadily declines due to the stress, leading to secondary effects including a suppressed immune system.

Here’s what’s happening. The electrical shock is the stressor, and both rats experience exactly the same amount of that stressful stimulus. Yet one rat feels in control of the stress. He can turn it off at will. On a psychological level, this makes all the difference. Let’s consider why that’s the case, and what it means for our ability to cope with the daily stress we all face in the human rat race.

Psychological Immunity to Stress

The stress we experience is based on our perception of what’s going to happen next. If we anticipate a threatening situation, our body releases stress hormones to prepare us to face the threat.

But if we believe we have control over a threatening stimulus, then we don’t need to prepare for that threat in the same way. We don’t need to be on full alert with the fight-or-flight response gearing us up for survival. How can we regain a sense of control when faced with stress and uncertainty?

Let’s return to the story of Viktor Frankl. Faced with unimaginable hardship, he had no idea how long the torment would continue. There was no guarantee of rescue, and many of his companions died of starvation, illness, or worse. What did he do differently to cope with the stress?

He changed the focus of his attention. Frankl searched for meaning and purpose in the smallest daily actions, like caring for a friend or saving a scrap of string that might be useful later. He also found long-term meaning and purpose in the idea of survival itself. He reminded himself continuously that surviving this hardship would be meaningful to his family and friends. They needed him to come back to them alive.

This change in focus—from the many uncontrollable aspects of life to the few controllable ones—can have a profound effect. That’s because our perception of reality is, to a large extent, created by the focus of our attention.

Are you facing the stress of an uncertain future? If so, it helps to focus on what you can control. Sometimes that means bringing the finish line closer by setting goals for today or this week instead of trying to figure out what you’ll do if you lose your job three months from now. Sometimes, it means making a list of 10 ways you can stay connected with friends and choosing the best one to put into action.

Our human tendency is to focus on threats and problems. For the sake of our emotional wellness, it makes sense to modify that automatic tendency. You can’t control the stressors that come your way, but you can influence the focus of your own attention. That’s why we recommend you focus on the things that give you back a feeling of control.

Want another tool to combat stress? Counterintuitively, one of the best things we can add to your toolbelt is an entirely different belief about stress—one befriending it instead of battling against it.

The Power of Your Beliefs

In her TED talk, psychologist Dr. Kelly McGonigal revealed an important insight that changed her own mind about stress. After decades educating people about the dangers of stress and imploring them to reduce stress for the sake of their health, Dr. McGonigal discovered an unexpected trend in the data.

When people believed stress was something bad that must be avoided, it had a far worse impact on their health. In contrast, among those who perceive stress as a normal part of pursuing goals, there was no correlation between higher stress and poor health outcomes.

Once again, how we perceive stress matters. If you believe stress itself is a threat, something you must reduce for the sake of your health, and yet can’t effectively reduce it, you feel trapped. You have no control, just like the rat getting shocked at random.

Feeling out of control makes us feel even more stress, perpetuating the harmful cycle. Perhaps it’s time to consider an alternative view of stress. What if we stopped seeing stress as something abnormal or threatening to your future health and instead thought of it as something that empowers us to be our best?

For instance, speaking in front of hundreds of people can be debilitatingly stressful. Many people try to fight stage fright, thinking the stress will make them more likely to stumble over their words and embarrass themselves. However, instead of thinking the stress is a bad thing that we must resist, we can think of it as an asset. A racing heartbeat for instance, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it’s a sign of the body sending more oxygen to the brain so you can do your best.

After we learn to see stress as something to harness rather than run from, we can take things one step further. Let’s see what happens when you pursue stress deliberately, on your own terms.

Stress for Success?

In his book, The Power of Full Engagement, peak performance coach Jim Loehr recommends oscillating back and forth between pushing hard and relaxing. Observing both athletes and executives, Loehr noticed that we engage more fully in our work if we push hard for periods of time and then pull back toward rest and recovery.

An athlete who knows there’s a short break around the corner is capable of pushing harder during periods of extreme exertion. And if you think about this in the context of your own life, it probably makes sense. It’s easy to push hard for the last two days of work before a vacation, or even the last hour of a typical workday. That’s because you know you’re about to get a break.When you intentionally push yourself outside of your comfort zone and schedule periods of rest and recuperation, something interesting happens—your capacity to endure stress increases. It’s as if you’ve created a new set point for what feels normal.

For example, an entrepreneur who feels constantly pressed for time during her nine-hour workday might experiment with doing a 14-hour workday once per week for three weeks. Each of these long workdays is followed by a shortened workday of only six hours. In this case, she is stretching her sense of what’s possible by working longer than what feels comfortable. Then she recovers, taking it easy the next day.

The effect is less stress. Can you guess why? She has expanded her sense of what’s possible. She feels in control of the stressor (time pressure to get things done), because she knows that if the worst comes to worst, she can put in a few longer work days to get caught up. Things no longer feel out of control.

Alternatively, she can practice timeboxing. This time management tool gives her better control over the focus of her attention when too many things are competing for her time. Timeboxing allows her to translate her highest priorities into blocks of time she’s reserved to get the most critical things done. Once again, the result is a feeling of control.

Since stress comes from feeling out of control, you can sometimes put yourself back in the driver’s seat, deliberately steering toward stress so you have greater control over deciding when to steer away toward rest.

Achieve More with Less Stress

You don’t have to choose between a healthy life and a life of full engagement with high, hard goals. You can have both.

The way to have both is to take control of the stress you put on yourself. By proactively seeking stress in forms that further your goals, you can change your set point for what feels overwhelming. Doing so will eliminate the feeling that stress is happening to you. It’s instead something chosen by you. You’re taking control of stress before it takes control of you.

If done correctly, as you steer toward stress, difficult challenges will begin to feel more like an adventure. Emotionally, you’ll experience a sense of thriving and empowerment as you navigate your way toward difficult goals rather than a feeling of being crushed by their weight. Then, when you steer away from stress, you’ll experience a deeper level of relaxed contentment that contributes to your well-being, both mentally and physically.

Bottom line—stress isn’t your enemy. It’s not even a bad thing. Stress is, in a very real way, what you make of it. You can take control of it, or you can let it control you. The choice is yours.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier