There are various ways of classifying lies: by their consequences, by the importance of their subject matters, by the speakers’ motives, and by the nature or context of the utterance.

Perhaps the most useful way to classify lies is by the people who tell them: the different types of liars. Understanding lies and liars can help us avoid getting duped as well as protect us from drifting into dishonesty ourselves.

Classifying the Types of Liars

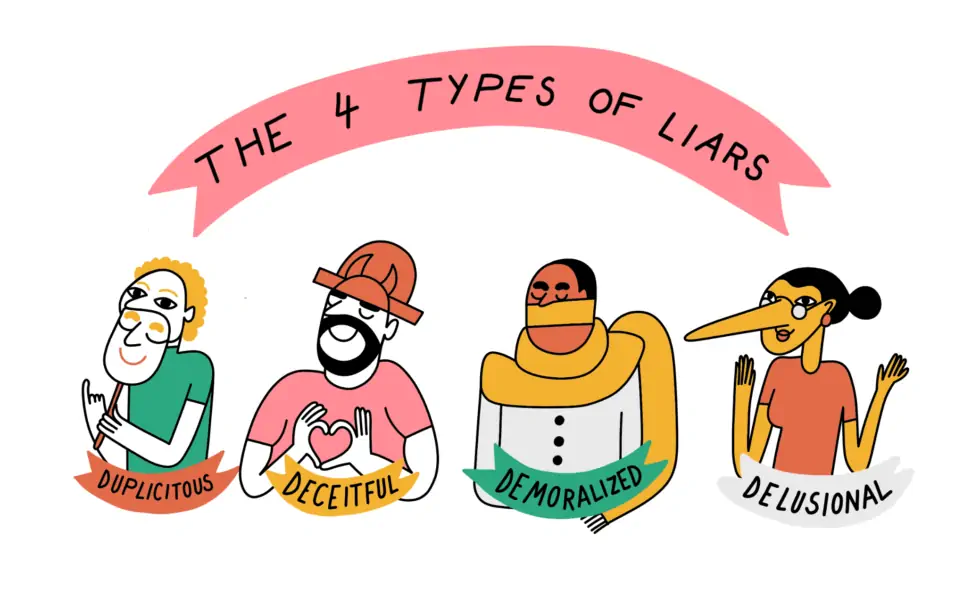

The diagram below is a taxonomy of types of liars, based on plotting their lies along two axes: their intended audiences (x-axis) and their subject matters (y-axis).

People can lie to two kinds of audiences: other people or themselves, and they can lie about two different kinds of things: facts (or what they believe to be facts) and their values.

We all know what it looks like when people lie about facts, but how does one lie about their values? What are values, anyway?

According to Russ Harris, author of The Happiness Trap, values are “how we want to be, what we want to stand for, and how we want to relate to the world around us.”

In my own words, values are attributes of the person you want to become.

To state your values in the here-and-now is to commit yourself to being or doing certain things in the future. For example, we might state our values include being a faithful spouse, a person who lives healthfully, or an adventurous individual. What we mean is that who we are and what we do in the future will have been shaped by our adherence to these precepts.

Free Distraction Tracker

Reclaim control of your attention today.

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

We can now explore four types of liars:

Which Type of Liar Are You?

(For entertainment purposes only)

Choose the option below that best describes you (or someone you know):

Deceitful liars: the types of liars who lie to others about facts

Lying to others about facts is prototypical lying. We’ve all done it. Children learn to lie around age three, and researchers believe it’s part of normal human brain development. Lying requires learning to see things from other people’s perspectives, developing what psychologists call “theory of mind.” Learning to tell an effective lie means getting into the other person’s head in order to tell them what they want to hear.

Fortune teller gets into her client’s head in order to tell them what they want to hear

Fortune teller gets into her client’s head in order to tell them what they want to hear

The good news is that we tend to grow out of telling childish lies for purely personal gain—for the most part. We still tell white lies as adults to maintain social relationships.

When was the last time someone greeted you with, “How are you?” and you responded with how you really felt? You likely said, “Great!” or “Fine!” even if you were having an awful day. This sort of dishonesty is expected. Yes, it is technically deceitful, but since both parties know you’re not supposed to respond with any substantive truth, you do it anyway.

Telling a white lie about how your day is going

Telling a white lie about how your day is going

Imagine what would happen if you responded instead, “Well, the world is falling apart, I’m starting to question the purpose of my existence, and I’m feeling bloated from the kale salad I ate. But how about you?”

In games like poker, being a skillful liar can help you win. In politics, knowing how and when to lie can be an advantage.

White lies aside, lying to others about facts for personal gain is corrosive to relationships and, if it’s a consistent pattern of behavior, can shut us out of people’s lives (and sometimes society in general).

Habitual liars get labeled as untrustworthy and earn a bad reputation that often precedes them, especially in our hyperconnected age. Whether it’s checking out someone to date or do business with, our online profiles and social connections increasingly help people keep tabs on our character.

Duplicitous liars: those who lie to others about their values

People can lie about their values just as they can lie about facts. They say they are committed to being someone or doing something, but their actions prove otherwise.

“Duplicitous” comes from the Latin word for “twofold” or “double” and is why we call this sort of liar “two-faced.”

Lying about values can be even more corrosive to relationships than lying about facts. When I state a commitment to being faithful or healthful or loving, I position myself as a certain type of person. I am telling people what kind of person I am now and in the future, so they can count on me to act in certain ways.

Some of the most important decisions in peoples’ lives are guided by this confidence—decisions to spend time with someone, to love them, to make sacrifices for them, to trust them with our money, our children, our careers, or our opinions. Lying about our values undermines this basic trust.

Lying about values compromises peoples’ abilities to make informed decisions because it limits their view of what the future has to offer. If you trust me, you are likely to adjust your behavior based on what I say. If I encourage you to invest in a particular stock or discourage you from applying for a particular job, you will choose to limit your future options based on my advice: you’ll forgo other investment opportunities or forego the one job in favor of others.

In the same way, if people trust that you have the values you say, they’ll forgo other opportunities to invest their time and attention elsewhere because they’re confident you’ll remain the person you say you are.

As in the case of lying about facts, the information age places limits on how long someone can sustain lying about their values. When it becomes evident that there is a disconnect between someone’s professed values and their actions, it is difficult to trust their word ever again.

Delusional liars: those who lie to themselves about facts

It’s not just other people we lie to. We also lie to ourselves. You might tell yourself that your curt response to someone wasn’t insensitive, or that you didn’t take more than your fair share of dessert, or that you contributed more to the team project than you did.

We constantly lie to ourselves and there’s reason to think that healthy psychological functioning involves some level of self-deception. However, not all self-deception is created equal.

There’s a difference between the commonplace lying that mentally healthy people engage in and the kind of self-deception that marks mental illnesses like schizophrenia or manic depression. There’s also a difference between certain types of self-deception and lies that erode our integrity.

In his novel, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky wrote, “Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others.”

Why do people lie to themselves? What motivates us to distort facts in our own heads?

The motives for self-deceit are various. They include insulating ourselves from uncomfortable truths and convincing ourselves of comfortable ones. Humiliated spouses try to convince themselves that their partners really aren’t cheating. Parents try to convince themselves that their children really aren’t badly behaved. Mediocre players try to convince themselves they’re really vital to the team. Many of us try to convince ourselves we’re more likeable, better looking, less biased, or more competent than we really are.

Lying to ourselves can also be a way of reconciling contradictory beliefs. Psychologists call the uncomfortable state of holding two conflicting ideas, “cognitive dissonance.” For instance, let’s say you meet members of a doomsday cult. (Stick with me, this is based on actual events.) The devotees profess to you and everyone they know that they are absolutely certain the world is going to end in 30 days. They’re so sure Armageddon is nigh that they quit their jobs, sell everything they own, and do everything their cult leader says. (It is, after all, the only way they can save their souls in the apocalypse to come.)

30 days pass, and thankfully the world doesn’t end. But now the cult members have a big problem. What will they do the day after the world was supposed to have ended? The cult members believed with all their hearts that the world would end, but it obviously didn’t. Would they renounce their beliefs on the spot, throw up their hands, and say, “Our bad! Let’s go get a Starbucks?” Not likely.

In the 1956 book, When Prophecy Fails, social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues described their study of a small group called the “Seekers.” The group believed in a UFO religion and professed with utter certainty that the world would end in a great flood on December 21, 1954.

When midnight struck and no cataclysm occurred, the group sat in stunned silence. Then, someone realized a clock was five minutes late. Oops! They sat awkwardly for a few minutes longer, awaiting imminent destruction. Obviously, nothing happened.

After four hours of nervous silence, something finally did happen. The group leader announced she received a message from an alien planet that told her, “The little group, sitting all night long, had spread so much light that God had saved the world from destruction.” Hooray!!

Clearly, the group members needed to believe a story to help them escape the facts. Lying to themselves was easier than admitting they were wrong all along.

Lying to oneself about an apocalypse that didn’t happen is silly, but the ability for self-deception can, at times, be a surprisingly valuable asset. Steve Jobs, for instance, was said to have a “reality distortion field” that gave him the power to mysteriously manipulate others into working on seemingly impossible tasks and timelines. By getting others to believe in his version of reality, they sometimes put their doubts aside and took his confidence on faith. According to his former publicist, Andy Cunningham, “When you worked with Steve Jobs, everything that seemed impossible he made possible, or he made you make it possible, which was even more important.”

Jobs’ mind-melting superpower included his ability to manipulate his own beliefs as much as others’. All the great entrepreneurs I’ve met have the power to activate their own reality distortion fields. How else does someone convince people it’s a good idea to invest money or their career into a crazy business idea?

Unfortunately, all the worst entrepreneurs also have this capability. Theranos founder and Jobs wannabe, Elizabeth Holmes, allegedly used her reality distortion field like a Jedi master of confabulation.

In politics, religion, and business, having a vision can motivate recruits, converts, and customers, and, while our conscience makes it difficult to lie to others, self-deception resolves cognitive dissonance by distorting our own view of reality. If we believe with enough fervor, we can motivate ourselves and others to create the future.

The difference between a prophet and a false prophet is not necessarily who is telling the truth, but rather who is better at convincing themselves and others to work at making their vision a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Demoralized liars: those who lie to themselves about their values

People deceive themselves about their values for many of the same reasons they deceive themselves about facts. Among other things, they want to see themselves as more diligent, honest, or trustworthy than they really are. They say they are committed to working hard, telling the truth, or keeping promises, but their actions say otherwise.

The pitfalls of lying about values are similar to those of lying about facts, but there is an added snare—lying to ourselves about values compromises our integrity.

The word “integrity” has its roots in the Latin word “integritas,” meaning “intact.” It describes a whole that isn’t weakened or compromised. A crack in a foundation compromises the integrity of a building; a crack in the hull compromises the integrity of a ship.

When the integrity of a whole is compromised, parts of it are divided from each other, and the whole is weaker as a result—a building is more likely to collapse, a ship to sink.

When we lie to ourselves about our values, we are introducing a division within ourselves. If we are insincere in our stated commitments, or if we fail to follow through on them, we create a rift in our lives—either between our words and our intentions or between our current intentions and our future actions. Either way marks a failure—either failing to act how we believe best or failing to embrace the values that are best in fact. The implication in either case is that we don’t fully respect ourselves; either we don’t take our values seriously, or we don’t take our actions seriously.

The same is true of the people we are now and the people we will become in the future. Recall that our values are a way of shaping our future—at least those aspects of it in our control. When we say we’re committed to being diligent, honest, or trustworthy, we’re saying our future selves will be structured by these commitments and that the people we’ll be in five, ten, or twenty years from now won’t differ in these respects from the people we are today.

Failing to live into our stated commitments disrupts the continuity between our current values and our future lives. If our actions don’t line up with our commitments, then either who we are today or who we become tomorrow represents a failure. Either our future fails to hit the target our current values are aiming at, or our current values fail to aim at the right future target. Whichever it is, we can’t look at ourselves—either the people we are or the people we’ll become—without witnessing a miss.

Our integrity (or lack thereof) impacts not just our own lives but others’ too. It’s hard to respect people who don’t respect themselves, and, as we’ve seen, failing to live with integrity is a way of disrespecting ourselves. It’s also hard to trust the word of people who don’t take their own word seriously, or to entrust responsibility to people who don’t respect their own agency.

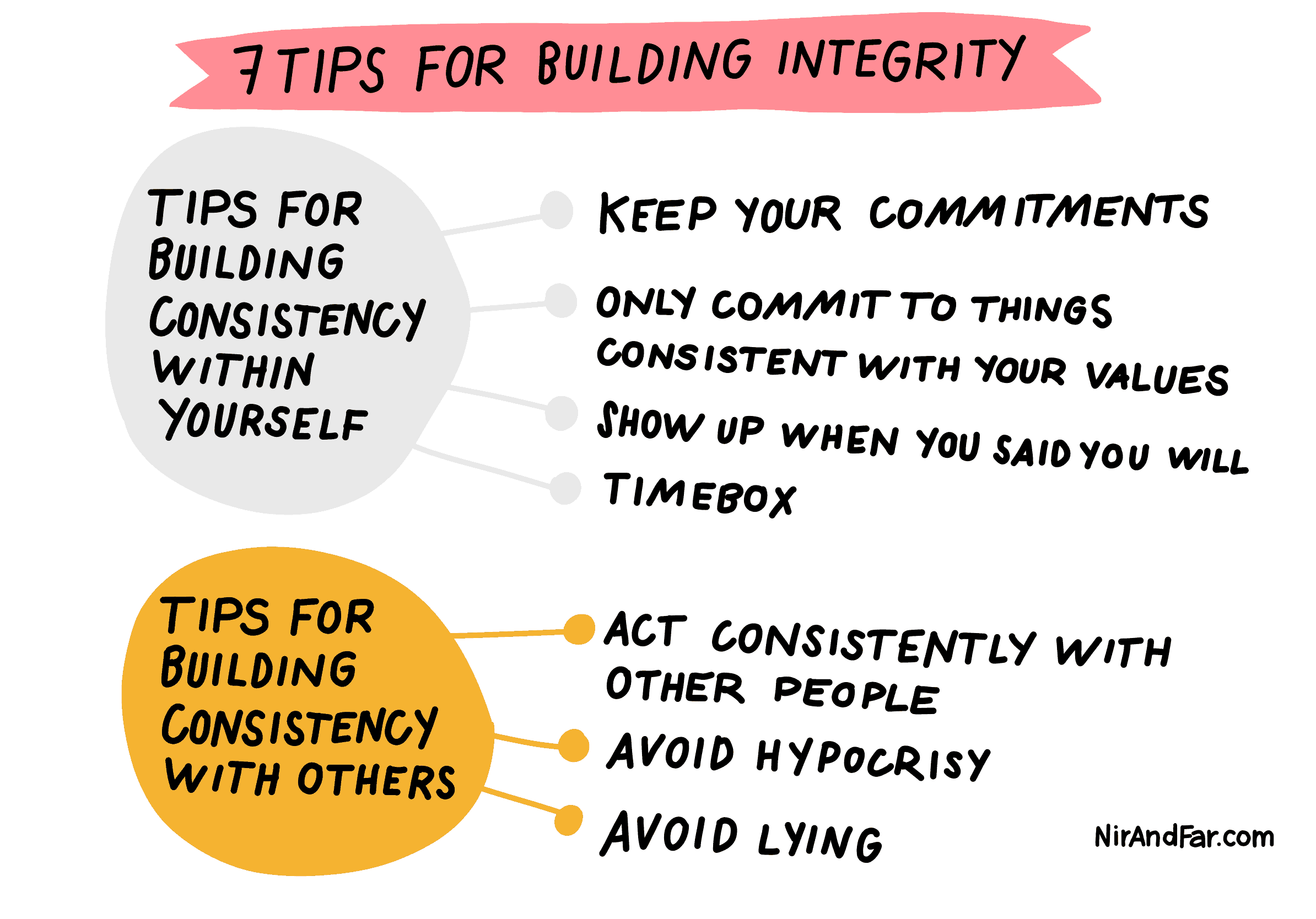

Tips for Building Integrity

Failing to live in line with our values disrupts the trajectory of our lives. When we think, feel, and act with integrity, by contrast, our lives stay on target. They arc into the future in line with our values and ensure we become the people we choose to be. They also provide the stability of character needed to build lasting relationships of trust and mutual respect.

How do we become people with integrity? In my book, Indistractable, I describe the practical steps we can take to build personal integrity by doing what we say we will do. Integrity requires consistency, so building integrity requires we follow-through on our word, to ourselves and others.

Here are 7 ways of act with integrity:

1. Keep your commitments and 2. only commit to things consistent with your values.

When we live with integrity, our actions are consistent with our words, and our words are consistent with our values. If you say you’re going to do something, integrity requires you to do it.

Failing on your commitments creates a rift between what you do and what you say, and internal rifts of this sort destroy integrity. They also destroy trust.

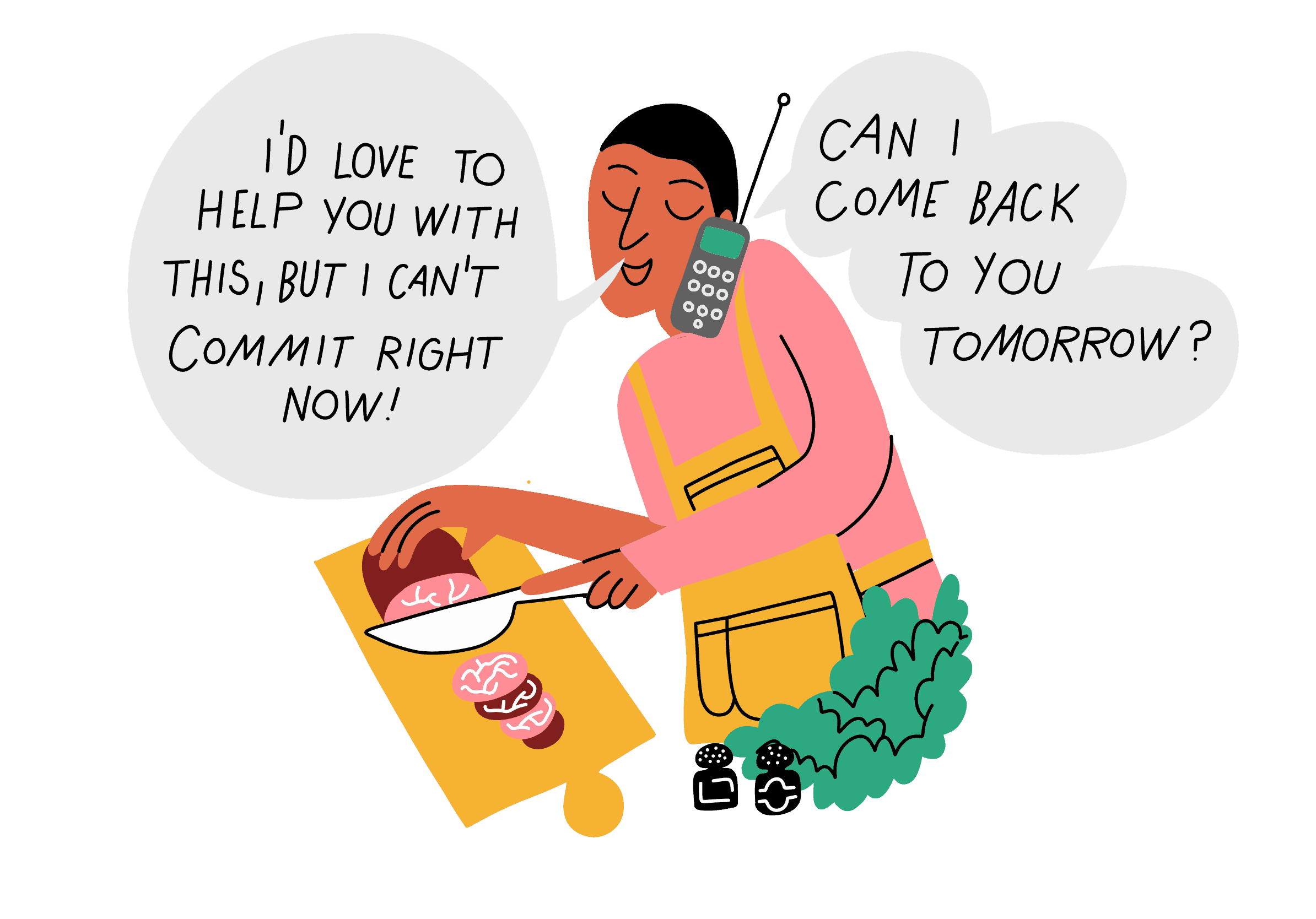

If you’re a people-pleaser, you may find yourself making promises to make other people (and yourself) feel good. You and they experience a bit of emotional relief when you say, “I can help you with that!” But if you don’t fulfill your promise later on, people will come to know they can’t rely on you; they’ll come to know you’re not someone they can trust.

Don’t make promises you can’t keep. If you’re unsure whether you can keep a promise, don’t make it. Instead, give yourself time to reflect on your reasons for wanting to promise something and whether you can really deliver. It’s fine to say, “I’d love to help with this, but I can’t commit right now. Can I get back to you tomorrow?” Who’s going to say no to that?

3. Show up when you say you will.

Our commitments include being on time. This is advice you likely got from your grandma, or in my case, my college professor. “Lateness is a sign of disrespect!” she intoned while wagging a finger at stragglers who slunk in late to lecture.

When you’re late for appointments, you’re effectively telling the people you’re meeting that they’re not very high on your list of priorities. You are, moreover, effectively telling yourself that your word isn’t worth very much, that no one—not even you—can rely on what you say. You can’t expect other people to respect you if you don’t respect yourself, and not showing up when you say you will is a way of signaling that you lack self-respect and that you don’t take your own word seriously.

4. Timebox.

Timeboxing is a schedule making technique. Being on time all the time can be difficult to manage when you have many commitments. Timeboxing is the most effective technique I’ve found for keeping your day on track.

The goal of timeboxing is to create a schedule that minimizes the chances of getting derailed by distractions.

Remember, you can’t call something a distraction unless you know what it distracted you from. Therefore, you can’t complain you got distracted without knowing in advance what you’re going to do with your time.

Timeboxing empowers you to spend your time according to your values, keeping your commitments to yourself and others.

5. Act consistently with other people.

It’s natural to make small adjustments to your behavior tailored to the immediate situation. You wouldn’t act the same way at your friend’s bachelor party as you would at a brunch with your new in-laws. But if you’re living with integrity, you won’t deviate from your core values no matter what the context.

6. Avoid hypocrisy.

Integrity demands that we judge other people and ourselves according to the same standards. There’s a word for people who don’t do this; they’re called hypocrites.

Hypocrites employ double standards: they use one set of standards to judge other people and a different set to judge themselves. They will, for instance, ruthlessly criticize other people for being late, driving too slow, or cutting in line, but feel justified in doing the very same things.

In some ways, applying different standards to people is natural. We don’t criticize our spouse for not knowing how to fix the drain, but we do criticize a plumber. Similarly, we don’t blame a casual acquaintance for failing to mention the bit of broccoli stuck in our teeth, but we would blame a close friend. Then there are people whose circumstances warrant different treatment: children, the disadvantaged, or those with mental or physical disabilities.

What sets hypocrites apart is that their double standards aren’t keyed to people’s social roles or circumstances. They apply different standards to people in the same circumstances they’re in, doing the same things they do.

This violates a basic principle of fairness: equals deserve equal treatment.

Hypocrisy is so corrosive to integrity that I’ve devoted a separate article to it. For our purposes, it’s enough to take home this point: don’t be a hypocrite!

7. Avoid lying.

No one wakes up in the morning and says, “I want to be deceived today; I want to be lied to, fooled, and taken advantage of.” We value the truth—at least for ourselves. If we lie to other people, we’re implicitly demanding that they tolerate something we wouldn’t tolerate for ourselves. That kind of double standard is inconsistent with integrity—a sentiment Shakespeare expressed in Hamlet: “This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man”.

This doesn’t imply that bending the truth can never be justified. If you’re sheltering a friend from a band of homicidal maniacs who ask point blank if he’s with you, lying to protect his life makes sense. If your aunt asks how her new hat looks, lying to protect her feelings makes sense as well.

But even though lying in some situations might be the right thing to do, people with integrity handle any decision to lie with extreme caution. They use it as a last resort, and are very clear about their reasons. They understand that lying is like using high explosives—without the appropriate precautions, it can demolish integrity.

Spotting liars isn’t always as simple as when someone lies to you and you know the truth — but with this guide to the different types of liars, you should be equipped to detect them all, and avoid becoming one yourself.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier