Nir’s Note: Ali Abdaal is a medical doctor turned entrepreneur, and the world’s most-followed productivity expert, with an audience of over 6 million across social media. His new book, Feel-Good Productivity, explores science-backed strategies that help you do more of what matters to you, in a way that’s enjoyable, meaningful, and sustainable.

The Pacific Crest Trail is not for the faint of heart. Spanning 2,650 miles of mountainous terrain in the western United States, it encompasses the entire longitude of America, from the deserts at the Mexican border to the mountains of north Washington. It’s renowned as one of the most arduous—and sometimes dangerous—hiking trails in America.

Every summer, thousands of intrepid walkers set off on the trail, knowing they won’t arrive at the Canadian border until five months later. For most people, this sounds like a hellish feat of endurance. For University of Missouri professor Kennon Sheldon, it sounded like a perfect opportunity for a psychological experiment.

Sheldon is a titanic figure in a recent wave of research into human motivation. At the turn of the millennium, many people thought that the great questions about motivation had been resolved. Since the 1970s, scientists have been aware of the two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is when you’re doing something because it feels inherently enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation is when you’re doing something because of an external reward—like making money or winning a prize. In the years since these two forms of motivation were theorized, countless studies have shown that when we’re intrinsically motivated to do something, we’re more effective and energized by doing it; and that extrinsic rewards can, in the long run, make us less motivated to do something for its own sake. Intrinsic motivation = good, extrinsic = bad. And that was that.

Except Sheldon had a hunch that things might be a bit more complicated. Starting in the 1990s, he wondered whether we were missing something crucial about the science of motivation. Yes, on the face of it, the evidence seemed clear that extrinsic motivation was ‘worse’ than intrinsic motivation. At the same time, though, our lives are filled with instances in which we clearly are motivated by extrinsic rewards—and motivated well.

Imagine a student (let’s call her Katniss) studying for exams. Katniss doesn’t enjoy the studying process itself, so her motivation to study isn’t intrinsic. For now, she’s motivated by something other than the pure joy of studying and learning.

How might Katniss be motivating herself to study? Here are some options:

- Option A: I’m studying because my parents are forcing me to. I hate this subject, but if I don’t pass, I’ll be grounded for a month. I need to study to avoid this terrible punishment.

- Option B: I’m studying out of a sense of guilt. I hate this subject, but I know that my parents have worked hard to send me to this school, and I know I should value the opportunity to do well to get into a good college. I feel anxious and guilty when I’m not studying, so I’m putting in a few hours of work each night for this exam.

- Option C: I’m studying because I genuinely care about doing well in school. Yes, I hate this subject, but I have to pass this exam to qualify for the classes I actually want to take next year. And I’m trying to do well in those because I really want to go to college, broaden my horizons, and maybe even apply to medical school someday. My parents aren’t forcing me to do any of this. Yes, they’ll be disappointed if I fail, but I’m not studying for them. I’m studying for me.

All three of these options would fall under the category of “extrinsic motivation”: in each case, Katniss isn’t studying because it’s inherently enjoyable. Instead, she’s studying to achieve some external outcome (avoiding punishment, eliminating guilt, or getting into her desired classes). But clearly, these three options represent very different attitudes towards work and life. Option C might even be quite a healthy form of motivation: one that encourages Katniss to work towards goals she values, even if the process isn’t intrinsically pleasurable.

Katniss’ example demonstrates that, in fact, not all extrinsic motivation is inherently “bad”. Like Katniss studying for the subject she hates, we all have to do things we don’t enjoy at times. And even when we start off enjoying something, if we do it for long enough, there will always be periods of hardship. In these moments, it’s rarely helpful to be told that if only we were enjoying ourselves more, we’d be able to persevere.

Which brings us back to Sheldon and the PCT trail. He began to suspect that anyone who embarked on the PCT trail was pretty likely to experience a collapse in intrinsic motivation at some point. What was motivating them to continue, he wondered?

So he decided to test it out. In 2018, Sheldon recruited ninety-two people who were interested in hiking the PCT. This group represented a mix of abilities. Seven had never backpacked before; thirty-seven had backpacked “a few times”; forty-six had backpacked “quite a lot”; and four had done it all their life. Before the hike started, Sheldon measured their motivation by getting participants to rate the accuracy of the following statements, each measuring a different type of motivation:

“I’m hiking the PCT because . . .”

- hiking the PCT will be interesting

- hiking the PCT is personally important to me

- I want to feel proud of myself

- I would feel like a failure if I didn’t hike the PCT

- important people will like me better if I complete the PCT

- honestly, I don’t know why I am hiking the PCT

When Sheldon looked at the data, he found that practically all the hikers saw drops in intrinsic motivation during the marathon hike. This isn’t surprising—when you’re walking 2,650 miles across freezing terrain over five months, it’s hard to enjoy every step genuinely.

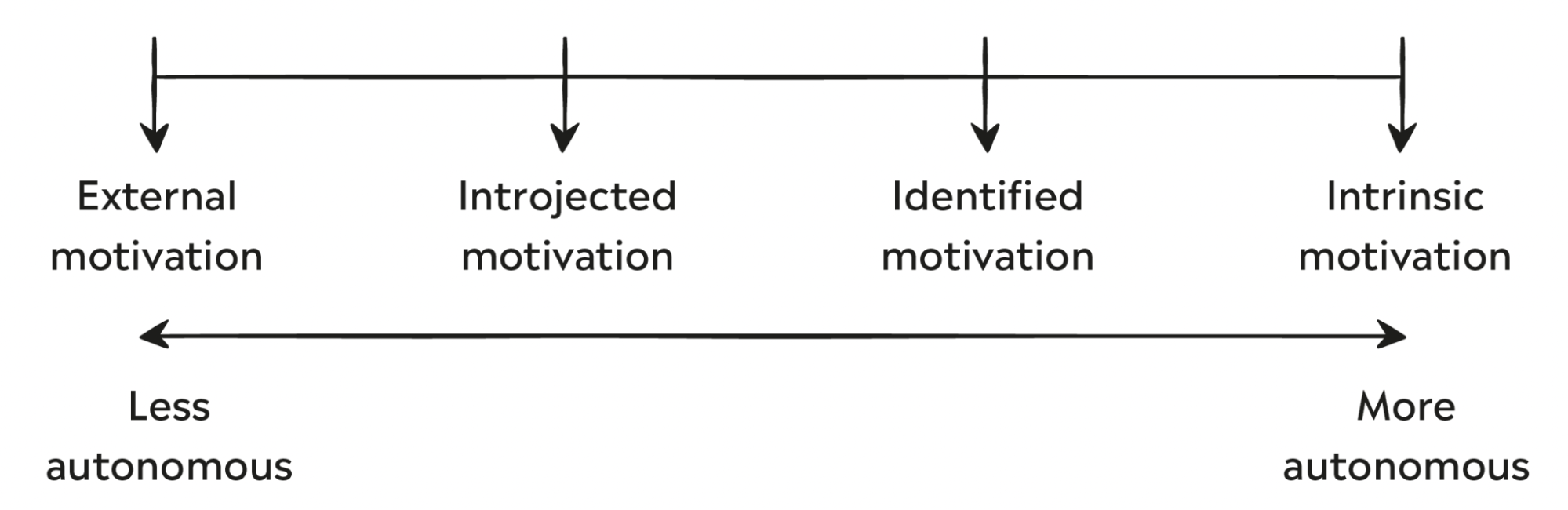

Sheldon was more interested in the form of extrinsic motivation the hikers turned to when their intrinsic motivation inevitably declined. By 2017, many scientists had begun to suspect that, as with Katniss studying for her exams, there were three discrete types of extrinsic motivation in addition to the purely intrinsic form. They fall on a spectrum called the Relative Autonomy Continuum (or RAC):

- External Motivation. “I’m doing this because important people will like and respect me more if I do.” People who highly rated this statement have high external motivation.

- Introjected Motivation. “I’m doing this because I’ll feel guilty or bad about myself if I don’t.” People who highly rated this statement have high introjected motivation.

- Identified Motivation. “I’m doing this because I truly value the goal it’s helping me work towards.” People who highly rated this statement have high identified motivation.

- Intrinsic Motivation. “I’m doing this because I love the process as an end in itself.” People who highly rated this statement have high intrinsic motivation.

External motivation is the form of extrinsic motivation that’s the least autonomous; instead of being motivated by any kind of internal force, we’re being controlled by the opinions, rules, and rewards offered by others. At the other end of the spectrum, identified motivation is the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation. Even though we might be doing something for the external reward associated with it, we value that reward or end goal—and crucially, that value was determined by us, not foisted upon us by others.

Using this framework, Sheldon spotted something fascinating about the PCT hikers. When inevitably, their intrinsic motivation waned through the course of the hike, the best predictor of their performance was the specific kind of extrinsic motivation they drew upon to help complete the trail. Using the data he collected on the hikers’ motivation, wellbeing, and hike performance, he showed that those who had higher levels of both introjected and identified motivation were far more likely to complete the trail. They managed to tap into these forms of extrinsic motivation to help sustain their progress even when the going got tough.

At the same time, Sheldon asked each of the walkers about their mood on the hike, using a series of well-established tests for Subjective Well-Being (SWB), psychology jargon for “happiness”. Therein lay his second intriguing insight: the only type of extrinsic motivation that corresponded with greater happiness was identified motivation. In other words, it was the hikers who motivated themselves by aligning their actions with what they truly valued and who not only completed the trail—but also felt happiest at the end of it. Sheldon didn’t use the term, but you might say that these hikers were experiencing Feel-Good Productivity.

This study hints at an insight into reducing our risk of misalignment burnout—the sort of burnout that arises from working towards goals that don’t ultimately match up to our sense of self. We feel worse—and so achieve less—because we’re not acting authentically. In these moments, our behavior is driven by external forces—rather than by a deeper alignment between who we are and what we’re doing. This alignment is something that only intrinsic and identified motivation can offer.

So how do we get more intrinsic and identified motivation in our lives?

Entire books have been written about increasing our intrinsic motivation—Daniel Pink’s Drive, for example, talks about how autonomy, competence, and purpose help drive intrinsic motivation. And the first three chapters of my book Feel-Good Productivity talk about the three energizers that drive intrinsic motivation: Play, Power, and People.

But a lot less has been written about boosting our identified motivation. The key to doing that, broadly, is to (a) figure out what really matters to you, and (b) align your behavior with it.

This is, of course, easier said than done. I go into much more detail about the specific methods to do this in the final chapter of Feel-Good Productivity, but I’ll summarize the strategies here in the interest of saving you time.

Download Our Motivation Workbook.

Get things done (even when you don't feel like it).

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

1. Figure Out What Really Matters to You

I’d recommend considering this on long-term, medium-term, and short-term time horizons.

Long-Term: The Eulogy Method

It might sound morbid, but it’s worth beginning with the end in mind. Specifically, your funeral. Simply ask yourself: “What would I feel good about someone saying in my eulogy?” Think about what you’d like a family member, a close friend, a distant relative, or a co-worker, to say at your funeral.

This method helps us understand the question of “What do I value?” from other people’s perspective. At your funeral, even your co-workers would be unlikely to say, “He helped us close lots of million-dollar deals.” They’d talk about how you were as a person—your relationships, your character, your hobbies. And they’d talk about the positive impact you had on the world, not how much money you made for your employer.

Now apply what you’ve learned to your life today. What does the life you want people to remember in a few decades mean for the life you should build now? So having started in this cheerful place, let’s bring things a little closer to home.

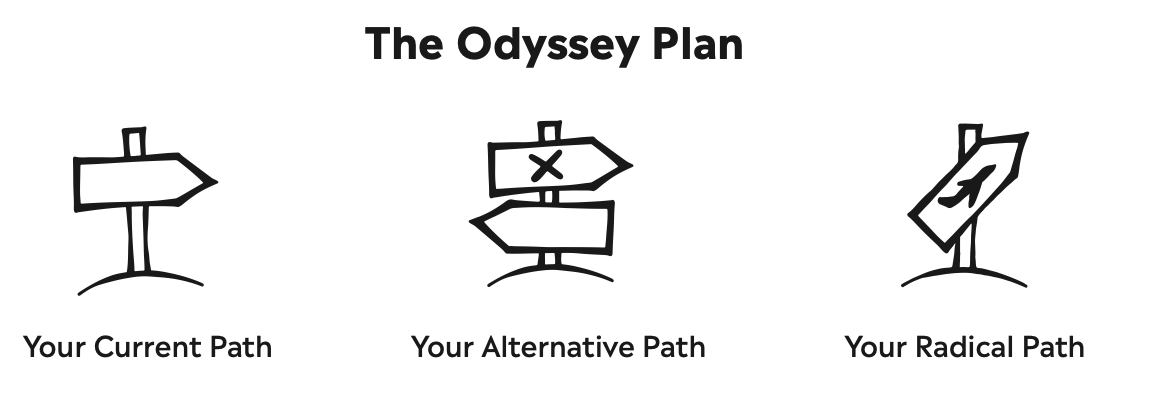

Medium-Term: The Odyssey Plan

This is a great exercise from the Design Your Life course run by Bill Burnett and Dave Evans at Stanford Business School. It revolves around a simple question: What do you want your life to look like in five years’ time? But instead of answering it at face value, consider approaching it from the following three angles.

- Your Current Path: Write out, in detail, what your life would look like five years from now if you continued down your current path.

- Your Alternative Path: Write out, in detail, what your life would look like five years from now if you took a completely different path.

- Your Radical Path: Write out, in detail, what your life would look like five years from now if you took a completely different path, where money, social obligations, and what people would think, were irrelevant.

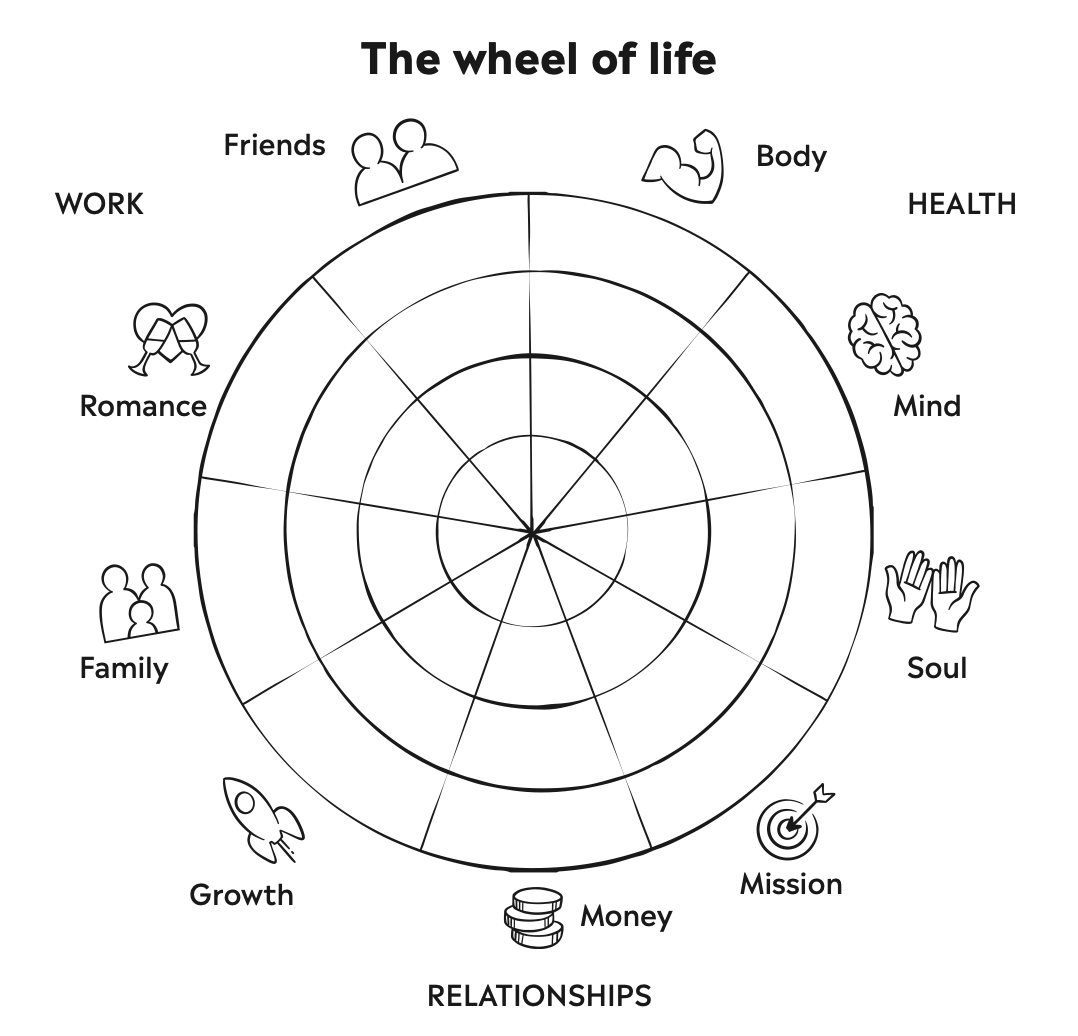

Short-Term: The Wheel of Life

This framework is similar to an exercise in Nir Eyal’s book, Indistractable, regarding examining your values. The idea is to first split up “life” into a number of different areas—I personally find a 3×3 separation to be the most helpful:

- Health: Body, Mind, and Soul

- Work: Mission, Money, and Growth

- Relationships: Family, Romance, and Friends

Next, you rate how aligned you feel in each area of your life. Ask yourself: “To what extent do I feel like my current actions are aligned with my personal values?” Color in the segment accordingly – if you feel fulfilled, fill it in entirely; if you feel completely unfulfilled, leave it blank. If you’re doing this without drawing it out physically, you might find it easier to just rate each area from 0 to 10, with 0 being “completely misaligned” and 10 being “completely aligned”.

In just a few minutes, you’ve done an audit of your life and identified the areas in which the actions you’re taking in the present moment do align with where you’d like to go, and, more importantly, the areas in which the actions you’re taking in the present moment don’t.

2. Align your Actions to What Really Matters to You

The exercises above should give you plenty of prompts to figure out what’s truly meaningful to you. So then, the final step to generating identified motivation is to align your actions with this (perhaps) newfound clarity to where you want to go.

For example, if you’re struggling to motivate yourself to work out, you might say to yourself—“I recognize that staying physically fit is important for my long-term health and happiness. Therefore, I’m not just working out to look good or because I feel I have to; I’m doing it because it aligns with my values and contributes to the life I want to lead.” This mindset shift, from seeing exercise as a chore to viewing it as a vital part of living your values, can be incredibly motivating.

Alternatively, if you procrastinate on a work project, reflect on how this task fits into your broader career goals. You might tell yourself, “Completing this project isn’t just about meeting a deadline; it’s a step towards mastering my craft and contributing to a field I’m passionate about.” By framing the task in the context of your professional aspirations and values, you transform it from a mundane obligation into a meaningful endeavor that resonates with your personal vision of success.

Or consider a common scenario like saving money. Instead of viewing it as a restriction, align it with your value of financial independence and security. Remind yourself, “I’m not just cutting back on expenses; I’m actively working towards my goal of financial freedom, which will allow me to pursue the things I truly care about without monetary constraints.”

These examples hopefully give you a sense of the transformative power of aligning your actions with your values. It’s not about blindly pushing through tasks or adhering to external expectations. It’s about consciously choosing activities that reflect your deepest values and aspirations, which helps infuse your daily routine with a sense of purpose and direction. This alignment is the essence of identified motivation—it turns routine actions into steps toward a fulfilling life, in line with your true self.

Again, there’s plenty more in the final chapter of my book Feel-Good Productivity, but in this post, I’ve tried to give you a few pointers about how you might generate more identified motivation for anything you’re struggling with.

A huge thanks to Nir for being a legend and giving me the opportunity to write this for you, his smart, lovely and rather good-looking readers. I hope you took something valuable from it 🙂

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier