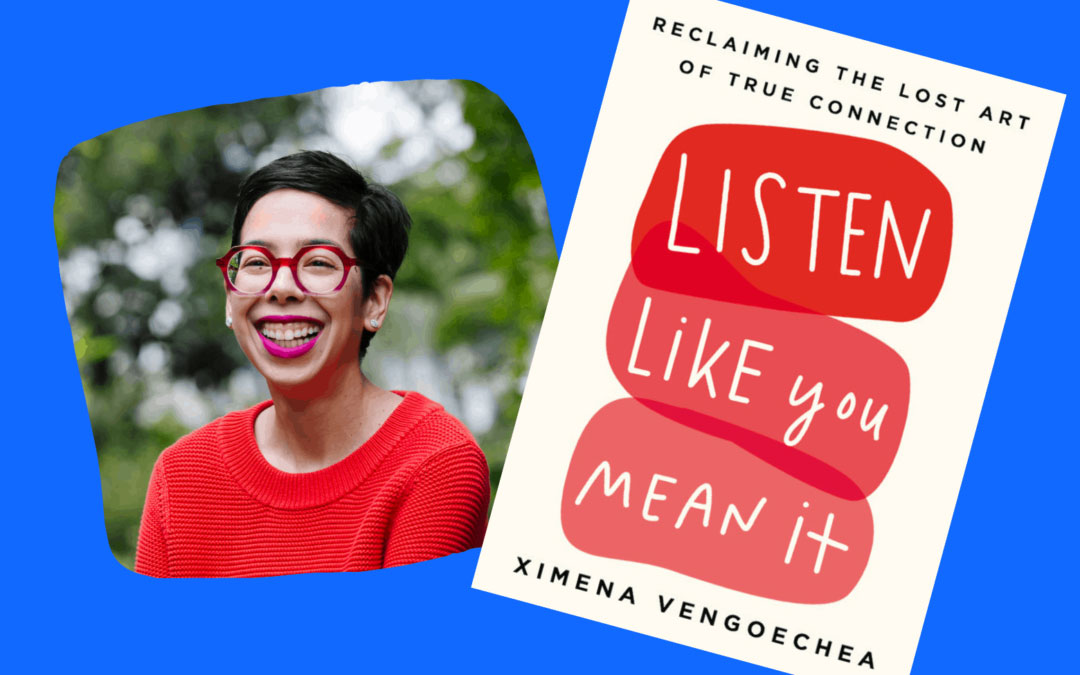

Ximena Vengoechea says we need to “Reclaim the Lost Art of True Connection.”

Ximena (pronounced “hee-men-ah“) is a writer and illustrator best known for her Life Audit project. Her work has appeared in Fast Company, Inc., The Washington Post, The Muse, and Newsweek. She also finds time to publish a lively bi-weekly newsletter with updates on tech, culture, writing, career, creativity, and other topics related to professional and personal development. Recently we chatted about her new book, Listen Like You Mean It.

Nir Eyal: Why did you write this book?

Ximena Vengoechea: As a user researcher, my job involves regularly interviewing strangers—users and prospective users of our products—to understand their needs, motivations, perceptions, and how our products might fit into their worlds. I’ve spent years doing this at companies like Twitter, LinkedIn, and Pinterest, where I managed a team of researchers. At a certain point in my career, thanks to the listening skills I had acquired, I started to feel more in tune with others in everyday conversations: at the office, I could read the room better, pick up on group dynamics quicker, and more easily recognize what others were feeling. At home, I was able to better recognize when my emotions were getting in the way of hearing others, and when others were holding back but had more to say.

It soon became clear to me that my training had (in a good way) started to make its way into my world. I wanted to help others reap the benefits, too. I wrote the book, Listen Like You Mean It, to translate the listening skills I acquired as a researcher from the lab to the real world and show how we can all become better listeners—whether that’s in the workplace, at home, with friends, or even among strangers—and build stronger relationships as a result.

NE: You’ve done some fascinating research. From what you’ve learned, what surprised you the most?

XV: When we think of listening, we think of focusing on others in order to hear them. But the more I learned about it, the more apparent it became that so much of effective listening is actually being aware of yourself: your own tendencies, habitual responses, what your body language may be communicating to others, the topics that hit on a tender spot and draw out an emotional response from you, even the environments, company, or time of day that can make your listening powers stronger or weaker.

For example, we sometimes believe we are listening to our conversation partner, but when we stop to observe ourselves, we realize we are actually listening to an internal monologue—about the to-do’s still left on our list, how upset we are about something that happened earlier in the day, or even composing an email in our mind without meaning to. We may feel we are staying present in conversation but already be planning a response before our conversation partner has finished speaking. We might jump in to complete a thought because we are (over) confident in our ability to predict what others are thinking, or because we are no longer comfortable with the topic at hand, and inadvertently shut others down in the process. It turns out that so much of what makes us effective listeners is how self-aware we are of what we are experiencing in the moment, not just our conversation partners.

NE: What lessons should people take away from your book regarding how they should design their own behavior or the behavior of others?

XV: Because self-awareness is so key to effective listening, I find it’s best to concentrate on designing your own behavior, rather than try to change someone else’s. In my book I talk about our “default modes” in conversation—habitual ways of showing up and responding in conversation. I identify 11 modes in the book.

For example, some of us are natural problem-solvers, always ready to find a solution. Others are the mediating type, and like to look at issues from all angles to avoid placing blame on others. These are worthy and generous characteristics, but they aren’t always what’s needed—reflexively going with our default mode can get in the way of hearing what our conversation partner really needs. That’s why sometimes we hear and solve for problems that don’t exist, or are so focused on looking at things from everyone’s perspectives that we miss that our conversation partner needs validation that their perspective is appropriate.

Instead, we have to take a hard look at understanding our default listening mode, spotting it when it surfaces, and stopping to ask ourselves if it’s called for. Even though we may find a certain kind of response encouraging or helpful, others may not; we need to listen for (and ask!) what others need from us in conversation.

NE: Writing a book is hard. What do you do when you find yourself distracted or going off track?

XV: Not glamorous, but I created a spreadsheet to track how and where I was spending my time on the book. It captures everything from how much time I dedicated to writing and illustrating (my book contains just shy of 100 illustrations), to book-related PR and marketing activities, to administrative tasks, too. The spreadsheet keeps me organized, but perhaps more importantly, it keeps me motivated—I gain a lot of energy and momentum from seeing the output of my efforts and my progress as I go.

With the spreadsheet, even if I hadn’t finished a chapter, I could see that I spent a given amount of time working on it and be satisfied by that. Tracking my tasks in this way also helped me to be more aware of when I was about to give into a distraction, or when it felt reasonable to take a break. If I start a task at 9am and am itching to take a break at 9:15, I know that I need to double down and focus. If that same urge comes at 9:45, maybe I feel okay hitting pause and regrouping again at 10am after a quick brain break.

NE: What’s your most important good habit or routine?

XV: I’m a morning person, so I’ve found it’s best to set myself up for early wins each day before the day gets away from me. I find it’s easier to be productive early in the day, before the day’s stressors or others’ needs shake up your to-do list. As a writer, I take the first few hours of the morning to write, including weekends when possible. Usually, after about three hours, I’m ready for a break (or lunch!) and can focus on other things for a bit. I get in another hour or so of work later in the day, but I reserve that time for more restful work, like illustrating or book research.

When I worked in tech, I followed a similar routine: I’d save my strategic thinking time for the mornings and schedule meetings in the afternoons. By 3pm I’m toast on deep, solo thinking (I don’t drink coffee), but I can easily respond, react, or collaborate with others.

When the pandemic hit, it took some time for my husband and I to recalibrate our usual routines, but we eventually found our rhythm: my writing block is earlier than it used to be, and my “free time” is largely spent with my 15 month old and spirited rescue dog, so “rest” looks different than it did pre-pandemic, but regularly carving out morning time for myself remains an important routine for me. Making progress early in the day makes the rest of the day go much more smoothly.

NE: Are you working to change any bad habits?

XV: I work in technology and have built a career around understanding human-computer interaction, and even though I know how mobile apps work to keep me on my phone, and have even written about the psychology of notifications that keep us coming back for more (with Nir!), it’s still difficult to step back from it.

Over time I’ve learned how to tame my smartphone usage by deconstructing my phone and being more thoughtful about what I turn to it for, and when. My daily phone time is down, but I’m still working on reducing the number of “pickups” a day—sometimes my hand unlocks my screen before my brain knows what’s happening.

As I become aware of that reflex, I’m trying to slow down and ask myself: Do you really need to check that email/refresh the news/etc?. Usually the answer is no.

NE: What one product or service has helped you build a healthy habit?

XV: Years ago, I learned texting, reading, or otherwise looking down at your phone puts the equivalent of about 60 pounds on your neck, and that scared me. Since then, I’ve developed two habits to help address that: listening to podcasts has been great for my wrists, neck, and shoulders, since I can look up and move my hands freely while listening.

The other service I love is the library. Reading a physical book doesn’t do nearly as much damage to your body as reading on your phone. I got into the habit of making a weekly trip to the library to pick out a book, which I’d then read during my commute instead of diving into my smartphone. In addition to being good for my body, it’s been a boon for my mental health: it’s much easier for me to focus, I enjoy the weight of a good book in my hands, and I tend to read about topics that are less stressful than whatever’s trending on Twitter. It also helps me feel more connected to my local community.

NE: What’s the most important takeaway you want people to remember after reading this book?

XV: Empathetic listening is not just an intuitive “you either have it or you don’t have it” trait—it’s a skill you can learn and develop, just like any other. We tend to forget this and focus more on other communication skills—what we are saying, how we are saying it, when we are saying it—but speaking is only half of the equation.

When we listen with empathy, we make more progress in getting to know each other and ourselves. Investing in developing this crucial skill improves your emotional intelligence, strengthens your relationships, helps you collaborate better, and ultimately feel more connected to others.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier