As part of a French study, researchers wanted to know if they could influence how much money people handed to a total stranger using just a few specially encoded words. They discovered a technique so simple and effective it doubled the amount people gave.

The turn of phrase has been shown to not only increase how much bus fare people give, but was also effective in boosting charitable donations and participation in voluntary surveys. In fact, a recent meta-analysis of 42 studies involving over 22,000 participants concluded that these few words, placed at the end of a request, are a highly-effective way to gain compliance, doubling the likelihood of people saying “yes.”

What were the magic words the researchers discovered? The phrase, “but you are free to accept or refuse.”

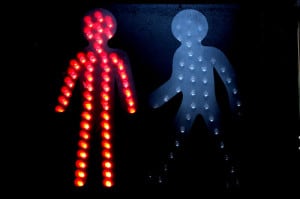

The “but you are free” technique demonstrates how we are more likely to be persuaded when our ability to choose is reaffirmed. The effect was observed not only during face-to-face interactions, but also over email. Though the research did not directly look at how products and services might use the technique, the study provides several practical insights for how companies can influence customer behavior.

Wanna and Hafta

Dr. Jesse Schell, of Carnegie Mellon’s Entertainment Technology Center, studies the psychology behind why people play. In addition to being CEO of his own gaming studio, Schell has poured over decades of research to try and explain why people spend countless hours entranced playing Angry Birds or World of Warcraft while at the same time dreading doing other things, like their day jobs or filing taxes.

At this year’s D.I.C.E Summit, Schell said the difference comes down to whether the behavior is a “wanna” versus a “hafta.” The difference between things we want to do and things you have to do is, according to Schell, is “the difference between work and play … slavery and freedom … efficiency and pleasure.”

Furthermore, Schell believes maintaining a sense of autonomy is critical to enjoying an experience. Schell points to the work or Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, whose Self-Determination Theory identifies a belief in one’s own freedom to choose as a key requirement for sustained motivation.

Unfortunately, too many well-intentioned products fail because they feel like “haftas,” things people are obligated to do, as opposed to things they “wanna” do. Schell points to neuroscience research showing “there are different channels in the brain for seeking positive consequences and avoiding negative consequences.”

When faced with “haftas,” our brains register them as punishments so we take shortcuts, cheat, skip-out, or in the case of many apps or websites, uninstall them or click away in order to escape the discomfort of feeling controlled.

Why Choice Works

So why does reminding people of their freedom to choose, as demonstrated in the French bus fare study, prove so effective?

The researchers believe the phrase “but you are free” disarms our instinctive rejection of being told what to do. If you have ever grumbled at your mother telling you to put on a coat or felt your blood pressure rise when your boss micro-manages you, you have experienced what psychologists call “reactance,” the hair-trigger response to threats to our autonomy.

However, when a request is coupled with an affirmation of the right to choose, reactance is kept at bay. It appears emancipating people from seeing a behavior as a “hafta,” opens them to viewing it as a “wanna.”

But can the principles of autonomy and reactance carry-over into the way products change behavior and form new habits? Here are two examples to make the case that they do, but of course, you are free to make up your mind for yourself.

Counting Calories

Take for example establishing the habit of better nutrition, a common goal for many Americans. Searching in the Apple App Store for the word “diet” returns 3,235 apps, all promising to help users shed extra pounds. The first app in the long list is MyFitnessPal, whose iOS app is rated by over 350,000 people.

When I decided I needed to lose a few pounds about a year ago, I installed the app and gave it a try. MyFitnessPal is simple enough to use. The app asks dieters to log what they eat and presents them with a calories score based on their weight loss goal.

For a few days, I stuck with the program and diligently input information about everything I ate. Had I been a person who logs food with pen and paper, MyFitnessPal would have been a welcomed improvement.

However, I was not a calorie tracker prior to using MyFitnessPal and though using the app was novel at first, it soon became a drag. Keeping a food diary was not part of my daily routine and was not something I came to the app wanting to do. I wanted to lose weight and the app was telling me how to do it with its strict method of tracking calories in and calories out. Unfortunately, I soon found that forgetting to enter a meal made it impossible to get back on the program – the rest of my day was a nutritional wash.

Soon, I began to feel obligated to confess my mealtime transgressions to my phone. MyFitnessPal became MyFitnessPain. Yes, I had chosen to install the app at first, but despite my best intentions, my motivation faded and using the app became a chore. Adopting a weird new behavior, calorie tracking in my case, felt like a “hafta” and my only choice was to either comply with what the app wanted me to do, or quit. So I quit.

Making Friends

On the other hand Fitocracy, another health app, approaches behavior change very differently. The goal of the app is similar to its competitors – to help people establish better diet and exercise routines. However, the app leverages familiar “wanna” behaviors instead of “haftas” to keep people on track.

At first, the Fitocracy experience is similar to other health apps, encouraging new members to track their food consumption and exercise. But where Fitocracy differentiates itself is in its recognition that most users will quickly fall off the wagon, just as I had with MyFitnessPal, unless the app taps into an existing behavior.

Before my reactance alarm went off, I started receiving kudos from other members of the site after entering-in my very first run. Curious to know who was sending the virtual encouragement, I logged-in. There, I immediately saw a question from “mrosplock5,” a woman looking for advice on what to do about knee pain from running. Having experienced similar trouble several years back, I left a quick reply. “Running barefoot (or with minimalist shoes) eliminated my knee pains. Strange but true!”

I haven’t used Fitocracy for long, but it’s easy to see how someone could get hooked. Fitocracy is first and foremost an online community. The app roped me in by closely mimicking real-world gym jabber among friends. The ritual of connecting with like-minded people existed long before Fitocracy and the company leverages this behavior by making sharing words of encouragement, exchanging advice, and receiving praise, easier and more rewarding. In fact, a recent study in the Netherlands found social factors were the most important reasons people used the service and recommended it to others.

Social acceptance is something we all crave and Fitocracy leverages the universal need for connection as an on-ramp to fitness, making new tools and features available to users as they develop new habits. The choice for the Fitocracy user is therefore between the old way of doing an existing behavior and the company’s tailored solution.

Conclusion

To be fair, MyFitnessPal does have social features intended to keep members engaged. However, as opposed to Fitocracy, the benefits of interacting with the community come much later, if ever.

Clearly, it is too early to tell who among the multitudes of health and wellness companies will emerge victorious, but the fact remains that the most successful consumer technology companies of our age, those which have altered the daily behaviors of hundreds of millions of people, are the ones nobody makes us use. Perhaps part of the appeal of sneaking in a few minutes on Facebook or checking scores on ESPN.com is access to a moment of pure autonomy – an escape from being told what to do by bosses and coworkers.

Unfortunately, too many companies build their products betting users will do what they should or have to do, instead of what they want to do. They fail to change behavior because they neglect to make their services enjoyable for its own sake, often asking users to learn new, unfamiliar actions instead of making old routines easier.

Instead, products that successfully change behavior present users with an implicit choice between their old way of doing things and the new, more convenient solution to existing needs. By maintaining the user’s freedom to choose, products can facilitate the adoption of new habits and change behavior for good.

TL;DR

– When our autonomy is threatened, we feel constrained by our lack of choices and often rebel against doing the new behavior. Psychologists call this “reactance.”

– To change behavior, products must ensure the user feels in control. People must want to use the service, not feel they have to.

– Attempting to create entirely new behaviors is difficult because these actions often feel like “haftas.” For example, unless someone already has a habit of counting calories, a diet tracking app can feel alienating, telling the user what to do and neglect to provide opportunities to get back on track if they slip-up.

– However, by making an existing behavior easier to do, a product can imply a choice more likely to be accepted. By making the existing behavior simpler and more rewarding, products give users the choice between their old way of doing things or porting their habits to the better, new solution instead.

– By catering to existing routines, products stand a better chance of changing user behavior as they move people to increasingly complex actions and new habits over time.

Thank you to Steph Habif, Ryan Hoover, Max Ogles, John Solomon and Mark Williamson, for reading early versions of this essay.

Photo Credit: marfis75

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier