Today, you can become a card-carrying member of just about anything: hotels, supermarkets, drugstores and pizza chains. If you’re in a store, chances are someone will ask, “Would you like to join our rewards program?”

Marketing professors, store managers and executives are still not sure how effective these initiatives are. One puzzle is the link between participation and loyalty. It’s not that strong. Millions of Americans are enrolled in at least one loyalty program, but just a fraction of them are dedicated customers. Typically, loyalty programs work only to the extent that they reward customers who are already loyal.

Another part of the mystery is the reward itself. Most loyalty programs offer additional perks to create a positive feedback loop — the more we shop in one store, the more we get in return, the less we’ll shop in another store. But in a world saturated with offers, it’s difficult to turn a reward into a habit.

Here’s one idea. Instead of asking, “What rewards should we give away?” ask “How should we give away a reward?” It might not be the reward per se, but how the reward is framed, and the steps customers must take to obtain the reward, that matters.

How to Frame a Reward

In 2004, marketing researchers Joseph Nunes and Xavier Dreze teamed with a local car wash in a busy metropolitan area. For one month, the researchers handed out loyalty stamp cards every Saturday. They used two different cards depending on the week. Customers on the first and fourth week received a card with an offer to “buy eight car washes and get the ninth one free.” The second group of customers received a card with a slightly different offer. They were awarded one free wash for every ten purchases, but they were also gifted two free credits.

In absolute terms, each deal was the same. Eight trips to the car wash earned one free wash. Yet twice as many people in the second condition completed the stamp card; having earned two credits, the feeling of progress nudged them to return. Nunes and Dreze term this tendency the endowed progress effect: We’re more committed to completing a goal when we have made some progress.

How to Frame Progress

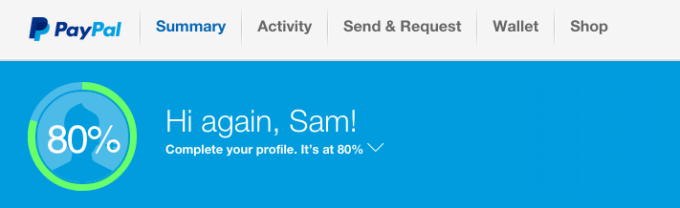

PayPal illustrates how complete my profile is with an easy-to-digest visual. By highlighting the progress I’ve already made — even though the “progress” is the mere act of signing up — I’m motivated to give them my phone number. No turning back now; I’m already 80 percent of the way there.

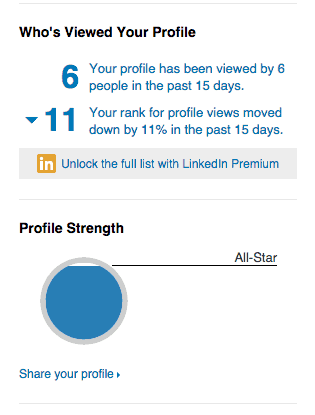

LinkedIn, where I can gauge my “profile strength,” is similar. My profile is nearly finished — but not quite — a compelling reason to “strengthen it.” Yet LinkedIn is more sophisticated than PayPal. It informs me that six people have viewed my profile in the past 15 days adding an element of social pressure. Notice the copy underneath this notification: “Your rank for profile views improved by 11 percent in the past 15 days.” With the feeling of progress, I’m more likely to click on the aptly placed “LinkedIn Premium” offer.

Candy Crush Saga, an attention-grabbing puzzle app, is different from PayPal and LinkedIn but employs a similar tactic to keep users engaged. If a user does not complete a level in the given number of turns, the game offers bonus items like “lollipop hammers,” “disco balls,” and more turns. However, there’s a price for the virtual goodies. Users must pay real money for a better shot at finishing the level.

It’s unlikely players would agree to pay at the beginning of a level. However, after spending time and energy, it’s a different story. Given the chance to beat that level you’ve been stuck on, these offers are much more appealing. What’s true of Candy Crush Saga is true of other popular games and platforms — they convert the users’ investment of time into money.

Framing as a Tool to Create Habits

An important step in creating routines is the gap between variable reward and investment. Variable rewards (new tweets, specials at the restaurant, deals at a retail outlet) keep us coming back for more, but they don’t necessarily lead to investment unless the product is designed to get the user to, “put something of value into the service.”

The variable reward on LinkedIn, for example, is the newsfeed and the notifications. Investment occurs when the user updates his profile, makes connections, and purchases LinkedIn Premium.

Smart framing can convince users to invest further in the experience, making it more likely they will return. It’s a subtle but psychologically powerful maneuver. Instead of trying to persuade customers to invest in a product or service, why not show them they’ve already invested?

Loyalty programs, in contrast, typically attract customers by offering better prices or superior products: ”Spend $100 and get $10 off!” or “Become a Platinum Elite member and get free upgrades!” are two familiar examples. Yet focusing on what a customer can acquire, instead of the time and money they’ve already spent, could be one reason these programs are ineffective. The trick is not strengthening the link between use and loyalty with better deals. It’s reinforcing the perceived relationship between use and loyalty. That starts with smart framing.

Nir’s Note: This post was co-authored with Sam McNerney, a freelance writer who focuses on psychology and business.

Photo credit: opensourceway

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Cancel the New York Times? Good Luck Battling “Dark Patterns”

- How to Start a Career in Behavioral Design

- A Free Course on User Behavior

- User Investment: Make Your Users Do the Work

- Variable Rewards: Want To Hook Users? Drive Them Crazy

- The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps