Social networks can help addicted users while leaving the rest of us alone. If they wanted to.

About five years ago, I sat down in a series of meetings with leaders from Reddit, Snapchat, Facebook, and other social media networks. My goal was to discuss social media addiction and how companies might self-regulate to curb it.

At the beginning of each meeting, I said something like, “You’ve got users on your platform who really want to use your products less, but they’re struggling to do so.”

Oddly enough, I explained, some people were actually using social media to help each other stop using social media! For example, some Facebook users had created Facebook groups specifically to help each other spend less time on the site. At that time, many tech executives didn’t know this was happening.

Then, I basically said, “If you’re able to find the users who want to stop using your products, you should try to help them. It’s an ethical obligation.”

Unfortunately, my advice fell largely on deaf ears. Now, regulators are trying to make all sorts of wacky new laws, including the Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology (SMART) Act, to get tech companies to reduce the risk of addiction.

There’s only one problem: these regulations almost always miss the point. Usually, the government “solution” is to ban specific features, like infinite scroll, autoplay, and gamification, but these bans aren’t likely to help addicts. Banning specific features is not going to make this problem go away; it will only make products less fun for everyone else. And by “everyone else,” I mean upwards of 90% of us.

Yeah. Contrary to popular opinion, only 3% – 10% of people are pathologically addicted to social media. For the other 90%, it’s a distraction, not an addiction. And in fact, for those of us in that 90%, thinking we’re “addicted” is counterproductive. Instead, we can and should take simple steps to keep this distraction at bay, along with all the other distractions in our lives.

There’s a better way to help.

Instead of banning the features that make these platforms fun, we should require social networks to implement Use and Abuse policies—systems designed to protect people who are vulnerable.

Specifically, tech companies should identify the users who want to stop using their products, then help them do that. We know that most people suffering from addiction try to stop on their own. They want to stop, and they know it—but they struggle to change their behavior. A similar pattern exists with social media overuse and abuse; there are people who want to stop, but they struggle to change their behavior.

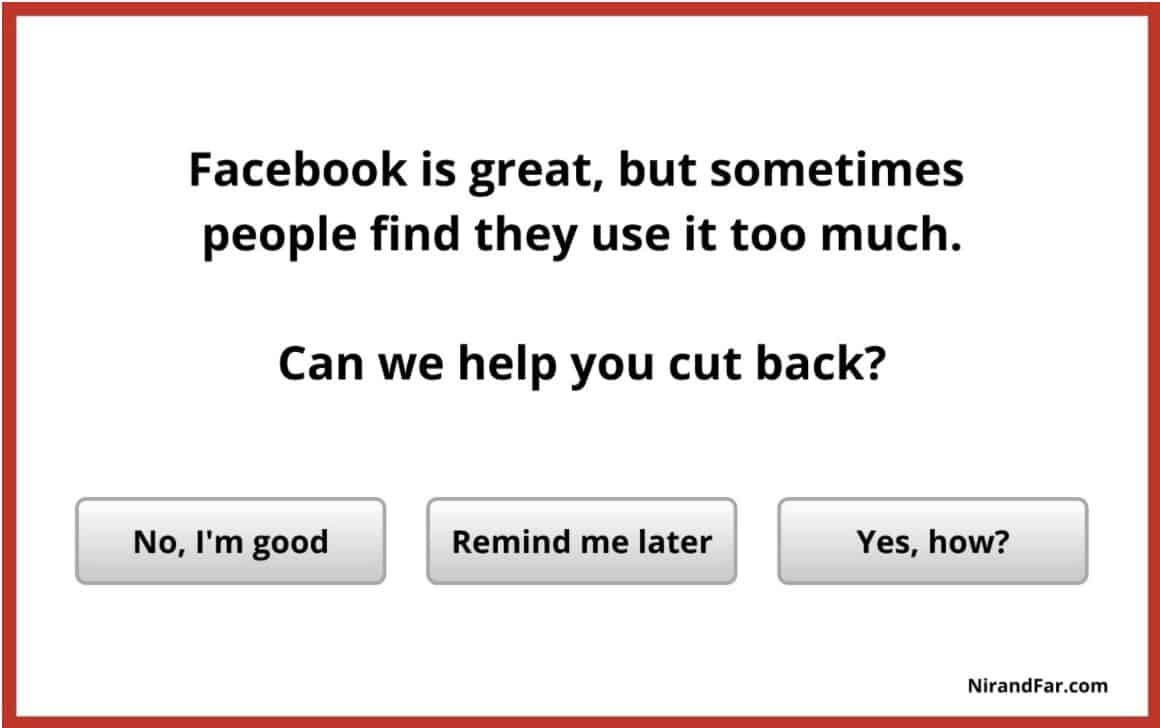

A Use and Abuse policy would make a real difference in these situations. One of the things I’ve proposed, illustrated by the image above, is a feature that prompts heavy users with an offer to help. After all, tech companies know how much time each user spends on their platform. So, when a super-heavy user pops up on their radar, they should ask, “You’ve been here a lot—do you want help cutting back?”

If the user says no, that’s fine. They should be left alone, at least for some time. Maybe that “super user” is a social media professional. Maybe they live in an isolated region where social media is the best way to connect with people. Plenty of people can use social media, even heavily, and suffer no adverse consequences.

But if the user says, “Yes, I do want help,” then the company should have a support structure in place for them. For instance, they could provide easy toggles for removing triggers that can lead to overuse, offer guidance on learning to moderate use and provide access to free online mental health services.

I’ve been suggesting this to tech leaders for years, anticipating that the call for regulation would continue to get louder over time. But for the most part, social media companies have disregarded the message, and they’ve failed to build Use and Abuse policies or systems to protect addicts.

It’s time for that to change. My hope now is that leaders will understand they have an obligation to protect people who abuse their products without making their services less useful for the rest of us. With nearly half of the world’s population using social media, implementing a Use and Abuse Policy is an ethical and business imperative that should no longer be ignored.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Cancel the New York Times? Good Luck Battling “Dark Patterns”

- How to Start a Career in Behavioral Design

- A Free Course on User Behavior

- User Investment: Make Your Users Do the Work

- Variable Rewards: Want To Hook Users? Drive Them Crazy

- The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps