Not more than 10 days after it launched, the MessageMe chat app company happily announced it had grown to 1 million users. The revelation captured the attention of envious app makers throughout Silicon Valley, all of whom are searching for the secrets of customer acquisition like it’s the fountain of youth. “Growth hacking” has become the latest buzzword, as investors like Paul Graham profess it’s functionally that matters.

Clearly, everyone wants growth. To someone creating a new technology, nothing feels better than people actually using what you’ve built and telling their friends. Growth feels validating. Growth tells everyone the company is doing things right. At least that’s what we want to believe.

What Exactly is a Viral Loop?

Good Growth, Bad Growth

Sometimes viral loops drive growth, because the product is truly awesome, while in other cases growth occurs for, well, different reasons. As an example of good growth, it’s hard to top PayPal’s viral success in the late 90s. PayPal knew that once users started sending money to each other, mostly for stuff bought on eBay, they would infect one another. The allure that someone just “sent you money” was a huge incentive to register.

PayPal nailed virality. Both sides of the transaction benefited from utilizing the platform and a classic network-effects business was born. In order for users to get what they wanted, they had to open an account and the product spread because it was useful and viral.

However, sometimes viral loops are less about the customer’s interests and more about short-term greed. When the product maker intentionally tricks users into inviting friends or blasting social networks, they may see growth, but it comes at the expense of goodwill and trust. When people discover they’ve been tricked, they vent their hatred and stop using the product. Unfortunately, we’ve all encountered the ways companies drive growth in deceptive ways known as “dark patterns.”

Viral Oops

Good and bad growth is relatively easy to identify. What is harder to decipher is the gray zone in between. A “viral oops” occurs when users unintentionally invite others, but when they look back on what happened, they blame themselves, not the app.

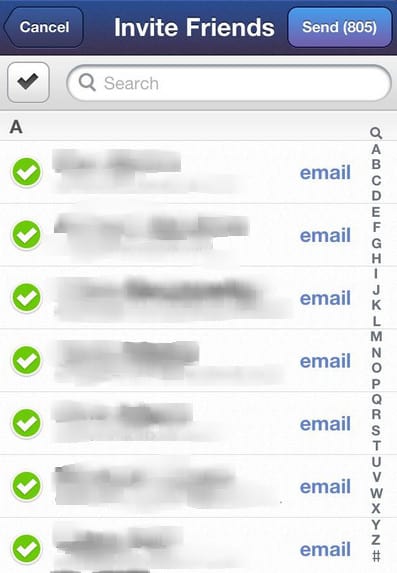

When MessageMe pre-selected everyone in my contact list as a default, I’m likely to think that only those who are un-checked will be invited. However, the opposite is true. With two taps, my list of hundreds of contacts gets swamped with a notification email personalized from my email account.

Could users really make such a mistake? After all, the send button is clearly labeled with the number of people who will be invited. I am also well aware of the convention that a check mark means the contact is selected and not the other way around.

However, say I was not in UX businesses? What if I were a tech novice living outside our little Silicon Valley bubble? What if I were slightly far-sighted? Or perhaps if English were not my first language (it isn’t)? Or maybe if I were attempting to make a quick decision while outdoors and couldn’t clearly see my dim screen? In any one of these scenarios, I could have easily triggered a viral oops.

The surprising math of viral growth reveals it doesn’t take many users to make this kind of mistake. Only 5 percent of users screwing up can get an app to a million downloads in two weeks, assuming the average user has 200 people in their contact list. The assumptions are for illustrative purposes (see note at bottom) but the point here is to show how powerful exponential growth can be, whether or not it is intentional.

Who Really Gets Tricked?

Admittedly, a careful review of the interface would reveal the user’s mistake. It’s hard to fault MessageMe. Though my requests for an interview were not returned, I assume their intent was not to trick anyone.

However, the example illustrates what makes the viral oops so troublesome. It is impossible to look into the minds of customers while they use an app. For all I know, MessageMe users intend to send the app to every single one of their contacts. But how would the app maker know if it was done in error? They wouldn’t.

A viral oops not only deceives the user, it fools the developer.

Unlike an intentionally deceptive technique, where the user gets angry and stops using the product or uninstalls the app, with a viral oops, users blame themselves. They’ll most likely keep the app and move on with life. With no metric indicating the user’s unintended mistake, the app maker is none the wiser.

A viral oops not only deceives the user, it fools the developer. There is no way to know if the invite was sent in error. Without an understanding of why users share the app, developers are liable to gloss over significant shortcomings that must be addressed for the app to achieve long-term success. Given how easy it is for us fallible humans to believe convenient truths, it is too enticing to interpret growth as validation instead of a mirage.

MessageMe is just one example of a hyper-growth app that was fooled by its own growth; I could have picked any number of other cases. In researching this article, I discovered multiple examples of the viral oops in companies large and small.

Developers should make sure they know why people are sending invitations to others and not be guided by growth for its own sake. App makers would be wise to be particularly careful in encouraging people to invite others before users really know how the app works. For example, prompting invites at first login is a remarkably common and potentially specious practice.

For creative people working on exciting new technologies, growth feels great. But we should be cautious of using techniques that have a high likelihood of being viral oops instead of viral loops.

—

Note: The virality math assumes a starting base of 1,000 users and a daily cycle time of 1 with a 10% invitation acceptance rate.

Thanks to Jules Maltz and Max Ogles for reading previous versions of this essay.

Photo Credit: Mel B

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Cancel the New York Times? Good Luck Battling “Dark Patterns”

- How to Start a Career in Behavioral Design

- A Free Course on User Behavior

- User Investment: Make Your Users Do the Work

- Variable Rewards: Want To Hook Users? Drive Them Crazy

- The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps