How Your Brain Sabotages Your Social Life—and Simple Ways to Fix It

Nir’s note: This guest post is from Dr. Ben Rein, an award-winning neuroscientist and author of the new book, Why Brains Need Friends.

When a friend invited me over last week, I found myself entering a predictable state of hesitation. I stared at my phone for a while, thinking, Should I bail? I gazed longingly at my couch, raising an eager hand toward my TV remote and imagining a romantic evening with my beloved screen. Shaking my head, I decided to follow through. “Be there in 15!” I texted back.

On the car ride, I suddenly felt oddly tired. Am I really up for this? I feel so drained … and this is only going to use up my energy! But as soon as I entered my friend’s house, my woes were forgotten. I felt terrific and, to my surprise, energized. I returned home feeling refreshed, and I wondered why I felt so reluctant to leave the house in the first place.

Despite that “epiphany,” I’ll probably go through the same dragging-my-feet process this weekend. What’s going on here? Why is socializing often so difficult?

In my new book, Why Brains Need Friends, I delve into the neurobiology of our social lives, sharing all I’ve learned as a neuroscientist who has studied social behavior for the past decade. The evidence is clear: social connection is immensely valuable. Community is a precious commodity for the biology that powers our brains and bodies. We truly need each other. In fact, socially isolated people are at higher risk for health issues such as dementia, heart failure, depression, and even diabetes. But that’s not all: Studies have tracked hundreds of thousands of people and found that those who had weaker social relationships were 50 percent more likely to die by any cause.

If that’s all true, then why the heck is it so hard for me to get out the door?

Well, researchers have revealed something else, too: Despite the immense value of connection, our brains have particular quirks that hold us back from interacting. Most people struggle to make the effort to socialize, and science is beginning to figure out why.

Here, I’ll share some of the key barriers and miscalculations that we’re prone to, drawing from Chapter 3 of my book. We’ll explore how your brain sometimes makes bad predictions about social situations and, more importantly, how you can overcome these natural limitations with simple, actionable steps. By understanding these subtle internal battles, you can dramatically improve your social life, boost your mood, and cultivate the kind of fulfilling connections your brain craves and deserves.

Your Brain’s Bad Predictions (And How to Outsmart Them)

In the modern world, we face a significant social problem. More than half of Americans are lonely, and our social circles are shrinking. The U.S. Surgeon General even declared an “Epidemic of Loneliness” in 2023. For such a clear problem, the answer seems equally straightforward: Interact more! But, annoyingly, it’s not that simple.

Most people are constantly surrounded by opportunities to connect with others. I bet that almost every day, you spend some time in a waiting room, bus, train, taxi, office, restaurant, bar, or park—likely near other people. However, for some reason, we tend to keep these moments to ourselves. Why not try to spark a conversation with the person next to you?

People should do this more often. It’s evidence-backed to boost your mood, and I can say from experience, it almost always elevates me. If we all did this more often, we would live in a happier, more connected, and more understanding society. Social interaction is highly beneficial for brain health. So what’s holding us back?

This is where those dire predictions come into play. The human brain is prone to all sorts of social miscalculations that can block these interactions from ever unfolding.

Bad Prediction #1: “This Won’t Be Worth It.”

We’ve all been there. For me, it just happened last weekend. Oftentimes, the thought of striking up a conversation seems … tedious. Or perhaps you anticipate it being awkward, dull, or simply not worth the effort. Science shows that this is common: We tend to underestimate how much pleasure or value we’ll derive from interactions.

Dr. Nicholas Epley, a behavioral science professor at the University of Chicago, demonstrated this in a series of studies, starting with the one presented here. Participants were invited to engage in a conversation with a complete stranger during their commute on a train or bus. But first, they were asked to predict how pleasant their ride would be. They consistently predicted meager enjoyment, expecting that a conversation with a stranger would have little effect on their experience. Yet, after the real thing, they reported being significantly happier than they had expected. This simple act of connecting far exceeded their pessimistic forecasts.

There’s your first strategy: Don’t wait for connection to happen; create it. If you can convince yourself to try it, you’ll be directly countering your brain’s tendency to undervalue social interactions, effectively “hacking” your biology for an instant mood boost.

Bad Prediction #2: “They’ll Probably Reject Me.”

If you’re starting to feel more motivated to socialize, you’ll likely bump into another paralyzing trap: the fear of rejection. Worries about getting the cold shoulder or an awkward ‘no’ can stop us in our tracks before we even try to connect. However, studies show that people tend to overestimate the likelihood of this happening.

In those same studies by Dr. Epley, participants guessed that more than half of the strangers they approached would reject their conversation attempts. The staggering reality? The rejection rate was 0 percent. Not a single person in the study was turned down by a stranger. Surprising? Not so much when you think about it from the other side. If someone politely started talking with you on your commute to work, would you refuse them? Personally, I’d be happy to pass the time in conversation. It’s certainly better than scrolling mindlessly on my phone.

Bad Prediction #3: “This Conversation Will Get Worse.”

You’ve successfully initiated a conversation, and it’s going well. Then, a subtle thought creeps in: It has probably peaked. It’s only downhill from here. This assumption often leads us to cut off interactions prematurely, potentially robbing ourselves of deeper connections.

In one study, strangers were paired for chats. After some talking, half of the pairs were abruptly cut off—no more chatting allowed. Meanwhile, the others continued talking for several more sessions. Those who were cut off were asked to predict how much they’d enjoy their interactions if allowed to continue. They said their enjoyment would worsen! It was as if they thought continuing a conversation would be too painful. However, the group that kept talking reported a steady level of enjoyment throughout all subsequent sessions.

We tend to wrongly assume that conversations have a diminishing “hedonic trajectory.” Don’t let a false prediction about declining enjoyment cut short a rewarding interaction. Give yourself the chance to experience the full, often sustained, joy of a positive social exchange.

Bad Prediction #4: “I’m Just Bad at Talking to People.”

Many of us harbor a quiet belief that we simply lack conversational prowess or that others are naturally better at it. This self-appraisal can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, making us avoid social situations where we feel inadequate.

A striking 2023 study asked people to rank their skills compared to others their age across various domains (reading, hygiene, work performance, etc.). People were generally confident, rating themselves above average in most areas. The only skill on which the average person rated themself below average was initiating and sustaining conversation.

This suggests a collective (and often unfounded) insecurity about our social abilities. Do you have true evidence that you’re bad at socializing? More likely, you’re getting in your own way by yielding to confirmation bias, the idea that we seek proof that confirms our insecurities but ignore proof to the contrary. So, try not to sweat it. You’re probably much better at talking to people than you think.

Knowing this bit of brain science helps us both recognize our unwillingness to socialize as a brain glitch and see beyond it. In those silent moments, whether on buses or in waiting rooms, while many of us are simply passing the time, we may be holding ourselves back unnecessarily. When we suddenly feel tired on the way to a friend’s house or the TV is calling our name, we should ignore those signals and plow ahead to our gatherings. Humans are intensely social beings; we have so much to gain from connecting with others. Still, we suppress these urges due to expectations that are probably wrong in most cases.

Free Habit Tracker

Design your ideal day and build your best life.

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Being around others sets off wonderful cascades within our brains and bodies. From being touched on your arm by a waitress to falling in love with your lifelong partner to simply thanking your driver as you step off the bus, these interactions stimulate amazing systems within us. What neuroscience has revealed about them is clear: We need each other.

In Why Brains Need Friends, I explain these systems and how they work to help you understand what’s truly at stake in our current battle against social isolation. If the book doesn’t pique your interest, that’s okay. I ask one thing of you: Please don’t let isolation win. Connect with others. Visit your loved ones. Don’t flake on friends.

I assure you, your brain will thank you.

Related Articles

- How to Protect Your Focus Without Burning Bridges

- One Question to Help You Get More Done

- The Pursuit of ‘Flow’ Is Overrated

- How To Disarm Internal Triggers and Improve Focus

- [Focus Guide] How To Make The Most Out Of Your Time And Your Life

- Your Ability to Focus Has Probably Peaked: Here’s How to Stay Sharp

- How to Clear Your Computer of Focus-Draining Distraction

- Un-Hooked: Increasing Focus in the Age of Distraction

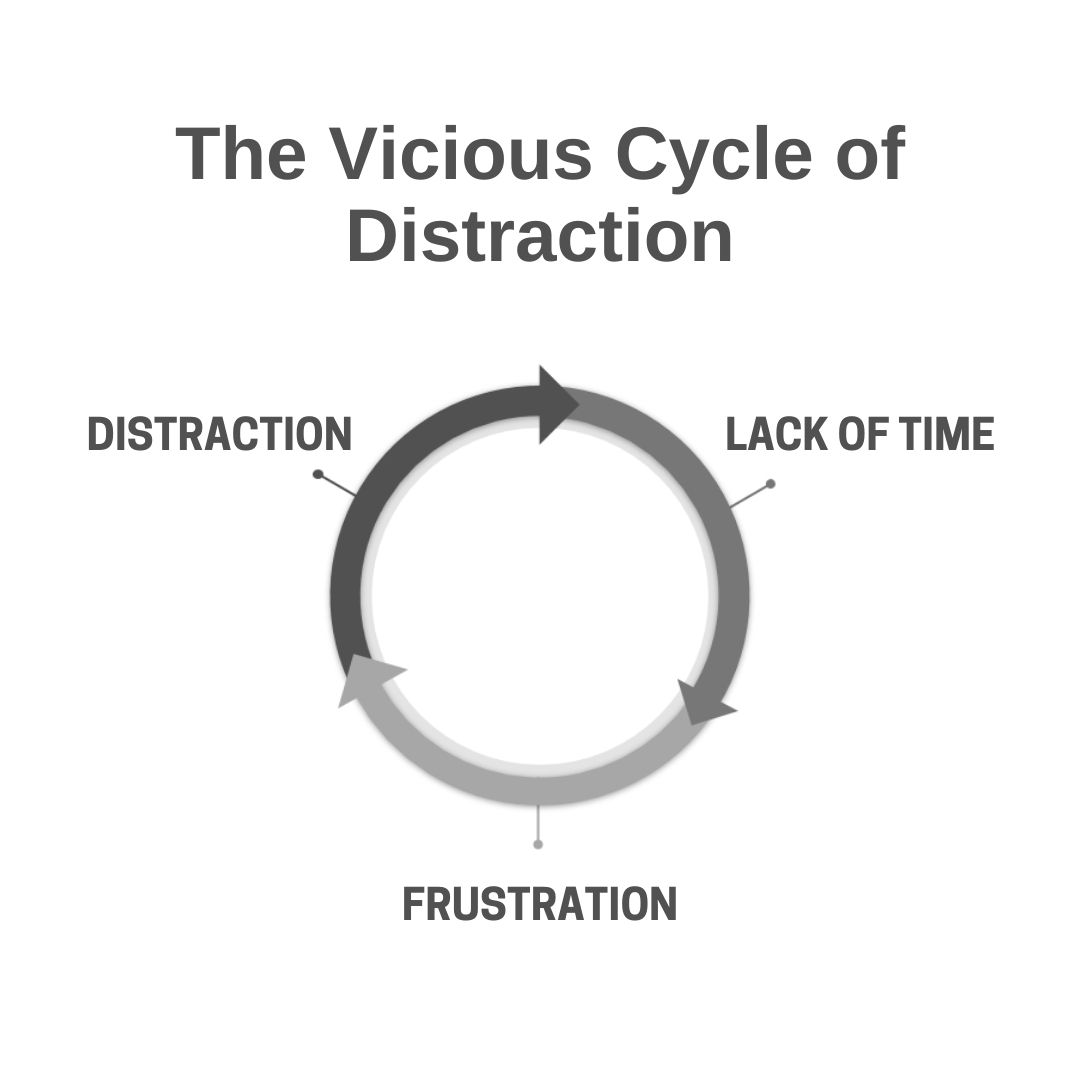

It’s one of those days. You wake up tired, having had a bad night’s sleep. An unresolved fight with your friend or partner is still gnawing at you, but you push it down, knowing you have to get the kids ready for school and finish a major project at work, plus tackle a

It’s one of those days. You wake up tired, having had a bad night’s sleep. An unresolved fight with your friend or partner is still gnawing at you, but you push it down, knowing you have to get the kids ready for school and finish a major project at work, plus tackle a