Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

Get my free and customizable schedule maker template to create your own timeboxed weekly calendar in an easy-to-use Google Sheet. Build a printable weekly schedule for college classes or work. You can merge cells and add your own images, icons and colors!

Many people bristle at the idea of using a schedule maker app. They don’t want restrictions and prefer the freedom to tackle things as they come up.

While an open day is wonderful on a vacation when you have nothing to do but relax, vacations eventually end. In the real world, there is work to finish, people to meet, and a family to nurture.

The fact is, we perform better under constraints. Weekly schedules give us a framework, while nothingness torments us with the tyranny of choice. Any artist will tell you about the challenge of staring at a blank canvas; a white page is the bane of every author. Likewise, an unscheduled day isn’t freedom. Rather, it’s a recipe for regret. When we don’t plan time in our day to do what really matters, our life quickly falls out of balance.

Whether battling distractions in school, at work, or with family and friends, we must make time for the important things in life. If we don’t plan what we will give our attention to, we risk having our time stolen by distraction. Learning how to schedule our time is an essential skill, as I describe in my book, Indistractable.

This guide will teach you how to do what you really want. It will teach you how to avoid getting sidetracked. You’ll learn tried and true methods backed by hundreds of scientific studies. Also, you’ll learn how to manage distractions, so you can get more out of each day, every day.

I designed this guide to teach you how to use a tool like the free schedule maker above. I’ve outlined the major sections below so you can jump to a particular area of interest. But I highly recommend scrolling through the entire story so you won’t miss anything. Whether you don’t know how to use a schedule creator, don’t keep a weekly/daily schedule, or have trouble sticking to one, you’ll find using these methods can completely change your life. It can help you finally get control of your time and attention.

This article contains the following:

Why Planning Your Day is Absolutely Essential

How do I Create a Schedule?

Free Schedule Maker Template

Take back control of your time and design your ideal day.

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Planning Your Day with a Schedule Maker Is Essential

Many people struggle with time management. But for most, the problem isn’t a lack of willpower or a deficiency of character. Rather, they lack an understanding of how to manage their day. A good schedule maker and a weekly or daily schedule template can make all the difference. But, you need to first understand its importance. Then, you need to learn the skills to create and stay in control of your schedule. The results can be remarkable.

Why You Should be Stingy with Your Time

Seneca, the Roman Stoic philosopher, wrote, “People are frugal in guarding their personal property; but as soon as it comes to squandering time, they are most wasteful of the one thing in which it is right to be stingy.” Although Seneca’s words are more than two thousand years old, they are just as applicable today.

Seneca, the Roman Stoic philosopher, wrote, “People are frugal in guarding their personal property; but as soon as it comes to squandering time, they are most wasteful of the one thing in which it is right to be stingy.” Although Seneca’s words are more than two thousand years old, they are just as applicable today.

Think of all the ways people steal your time. Your plan was to wake up and pray or meditate. But your teenage daughter can’t find the shirt she wanted to wear for school today. What do you do? You abandon your plans to join the hunt. Or you make breakfast and your toddler wanted oatmeal instead of eggs, so you remake the meal. Then you get to work. You sit down at your desk and decide to spend some time working on that new client proposal. But then Jim from Accounting drops by to say “hi” and asks you how your weekend was.

Twenty minutes later, Jim leaves and you finally open your laptop to get some work done. That’s when you see your email inbox is overflowing with thirty new messages. You start plowing through a few of the most urgent ones only to get a text on your phone from your colleague. “Are you free?” the message reads. “Can you join us for this client meeting?”

You decide to address your messages later so you attend the client meeting only to discover you weren’t really needed there. Hoping no one notices, you decide to do a little email checking on your phone. Just then, a little red icon appears on the Facebook app. Curious, you open the app. Wouldn’t you know it! Your old roommate from college just landed her dream job; well, you’ve just got to leave a message. It’ll only take a sec.

The entire day goes by like this. From breakfast to afternoon to the way home, you’re swinging from task to task at someone else’s whim. You’re reacting to demands on your time that distract you from, wait, what was it you were supposed to do this morning? Oh yeah, the new client proposal. Maybe tomorrow.

Of course, other people love the fact that you pivot to their priorities and away from your own. Your employer loves knowing you’ll respond to every email, even if it means working long nights and weekends. Also, your family loves knowing you will do things for them they could have done themselves. And finally, your daughter could look for her own shirt and your little one could deal with the fact that it’s eggs today. As for the technology companies, oh boy are they happy! Facebook and Twitter love the fact you’ll drop everything every time a notification pops up.

Why do we make decisions that lead to this sort of overworked, over-stressed, and ultimately unproductive day? Our instinct is to claim we just don’t have enough time in the day to get everything done, but that’s not really true. The average American spends 5.5 hours per day on leisure. Perhaps you’re thinking there’s no way you have that much free time. Just add up all the time you spend browsing the web, watching TV, and doing other miscellaneous non-work related tasks, and chances are you’d find the time. This is the ultimate irony of distraction—we go through life in a frazzled race, trying to get things done, while accomplishing few of our priorities, and then, when we do spend time on leisure, we don’t even enjoy it.

Seneca noted that people protect their property in all sorts of ways. They use locks, security systems, and storage units—but most do little to protect their time. A study by PPAI Research found only a third of Americans use a daily schedule. This means the vast majority of people wake up every morning with no real plans for how they want to spend their day. They don’t guard their most precious asset: their time. It’s just waiting for someone to steal it. The fact is, if you don’t plan your day, someone else will.

What is the Difference Between Traction and Distraction?

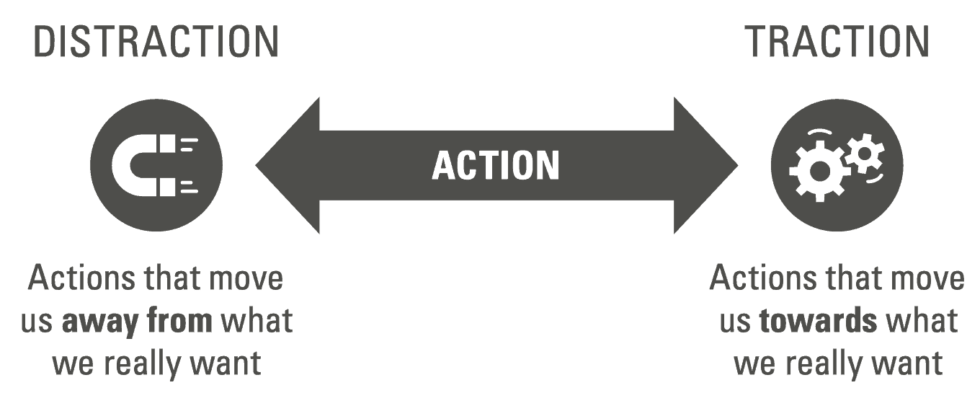

A distraction is something we do that moves us away from what we really want. The opposite of distraction is traction. Traction is something we do that moves us towards what we really want. The difference seems obvious but distraction has a sneaky way of tricking us.

At any given moment, it’s hard to tell whether we are moving towards or away from what we really want. Checking your work email may feel productive in the moment, but when you really need to focus your attention on a big project you’re neglecting, you’re bound to regret the time you wasted cleaning out your inbox.

The difference between traction and distraction is intent. Any action can be either a distraction or traction depending on what we intend to do with our time. Relying upon our feelings in the moment is too risky. The only way to truly know what we want is to plan ahead.

In my research and consulting work, I’ve heard countless people tell me how difficult it is to manage their time. But when I ask them what they got distracted from, they have trouble answering the question. They don’t recall what they planned to do. When I ask them to show me their schedule planner so I can see what they intended to do, they show me a calendar full of white space. If there is only one takeaway, it’s this: you can’t call something a distraction unless you know what it is distracting you from. If you don’t schedule your day, you can’t possibly know the difference between what you intended to do and what was a distraction.

In the next section, we’ll dive into how to create a weekly schedule template and keep to it. If you find yourself enjoying this guide to using a schedule maker, you’ll likely enjoy my other writing. I frequently share new research on the science of behavioral design through my free email newsletter.

To join, click here now.

How do I Create a Weekly Schedule?

A schedule maker is an app for building a weekly template for how you intend to spend your time. Here’s how it stops you from getting sidetracked: with a weekly template in hand, you’ll always know the difference between traction and distraction. If you find yourself doing what you planned, that’s traction. Anything else is a distraction.

There’s nothing wrong with scrolling Instagram, playing a video game, or watching Netflix, as long as that’s what you intended to do. Taking a break can be good for us. It’s when we do these things unintentionally that we get into trouble. For this practice to work, you must schedule every minute of your day on your schedule maker. This technique is called, “timeboxing” or making a “zero-based calendar.”

Does making a schedule guarantee you’ll never go off track? Of course not. After years of using this method, I still go off track from time to time. The point is to help you identify distraction so you can refine and improve how you spend your time in the future. Knowing you’ll slip-up is the secret to sustainable schedule making. Every time you fail, you have an opportunity to learn, adapt, and improve how you use your time to better accomplish what you want.

Conversely, if you think of a schedule as rigid, you’re more likely to throw it out the first time you get sidetracked. If you think of it as something you can continually improve, you increase the odds you’ll keep with it. You tailor it to your needs by adjusting it over time. Of course, you wouldn’t want to make changes on the fly—that would defeat the purpose of sticking to a schedule. Instead, you need a built-in way to regularly review and revise your schedule to make sure it’s still working for you.

Using a schedule maker involves three basic steps:

- turn your values into time

- make a template

- sync with stakeholders

1. Turn Your Values Into Time

April once struggled with her schedule, or the lack thereof. She works in ad sales at a large tech company in Manhattan. She used to hit her aggressive sales quotas year after year, but not anymore. The days of calmly and confidently representing her company and products were gone and so was fostering deep relationships with her clients. Instead, her friendly disposition had turned bitter. The mounting pressures to sell more and do more in pursuit of a management role had taken their toll.

Those pressures infected April’s schedule. This manifested itself in more meetings, more unplanned conversations, and more emails. As those distractions grew, they crowded out quality time to focus on her priorities. It kept her from taking care of her customers, closing more sales, and demonstrating greater results. But striving to be more productive haunted April and was ultimately making her miserable. It was also causing her to neglect important people in her life like her family and friends.

If you want to know what’s important to someone without asking them, where would you look? The German philosopher and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe thought of it this way: he believed the way someone spends their time can tell you everything. “If I know how you spend your time,” he writes, “then I know what might become of you. ”

If you want to know what’s important to someone without asking them, where would you look? The German philosopher and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe thought of it this way: he believed the way someone spends their time can tell you everything. “If I know how you spend your time,” he writes, “then I know what might become of you. ”

When it comes to using a schedule maker and planning your schedule, where do you begin? You should begin with your values. According to Russ Harris, a physician, therapist, and author of The Happiness Trap, values are “how we want to be, what we want to stand for, and how we want to relate to the world around us.” Values are attributes of the person you want to be. For example, your values may include being an honest person, being a loving parent, or being a valued member of a team. You never achieve your values any more than finishing a painting would let you to achieve being creative. Values are not end goals but rather guidelines for your actions.

The trouble is, we don’t make time to live our values. We unintentionally spend too much time in one area of our life at the expense of others. For example, we get busy at work at the expense of living our values with our family or friends. If we run ourselves ragged caring for our kids, we neglect our bodies, minds, and adult friendships. This keeps us from being the person we desire to be. If we chronically neglect our values, we become someone we’re not proud of. Our life feels it’s out of balance and diminished. Ironically, this ugly feeling makes us even more likely to seek distractions. We want to escape from our dissatisfaction without actually solving the problem.

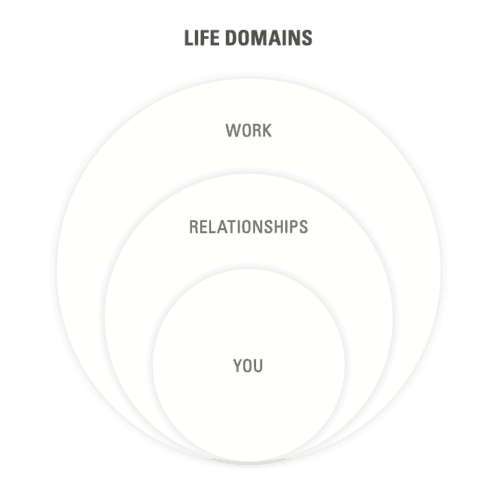

Although each of us may subscribe to different values, it’s helpful to categorize them into three overlapping life domains. These three domains describe where and with whom we live out our values. Most importantly, they give us something we can use to plan ahead. They help us take control so the way we spend our time becomes an authentic reflection of the person we want to be.

This concept is thousands of years old. The Stoic philosopher Hierocles showed us the interconnected nature of our lives using several concentric circles At its center, he placed the human mind and body. The next ring represented family. Fellow citizens and country men were next with all humanity in the outermost ring.

More recently, Daniel Goleman, author of Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence, relates the domains of our life to how we split our attention. Goleman describes “inner,” “outer,” or “other” focus, aligning with self, others, and the world around us. Successful people, Goleman claims, maintain the “triad of awareness” because “a failure to focus inward leaves you rudderless, a failure to focus on others renders you clueless, and a failure to focus outward may leave you blindsided.”

Hierocles and Goleman emphasize the importance of turning our values into time to define what matters most to us. Inspired by their examples, I created a way to visualize the three life domains where we spend our time.

The three life domains: You, Relationships, and Work

April’s problem was her lack of a structured schedule in line with her values. Her troubles were compounded by the self-limiting belief that she, and not her management of time, was the issue. “I’m too slow,” she told me one day as we ate lunch. “I see how other people are; they get so much more done than I do.”

There was nothing wrong with April. She wasn’t “slow.” She just didn’t have the right tools for her new role. Jumping from client to client without a schedule worked all right in her early years on the job, but now that she wanted to climb the corporate ladder, she needed a better way to manage her day. She’d have to design a schedule that allowed her to stay in sync with the stakeholders in all three domains of her life. To do that, I advised April to embrace a new way of working.

2. Make a Weekly Schedule, Budgeting Time Like Money

There’s an amazing line in the movie Top Gun, a favorite from my teen years. Maverick and Goose, two renegade airmen played by Tom Cruise and Anthony Edwards, are reprimanded by their ship’s captain. They risked their lives to help a fellow pilot in distress return safely to their aircraft carrier. But the captain, seemingly more concerned about the safe return of their F-14 fighter jets, barks out, “Son, your ego is writing checks your body can’t cash!” What a line!

We all want to be the hero of the movies playing in our heads. We think we can do it all and write checks with our time, forgetting they’ll soon be cashed. But unlike a bank account with a finite balance, we have a tough time keeping track of the time we have left to give. And when we make the grave mistake of over-allocating our time, the stakeholders in our lives suffer. That’s why, in the same way we budget our dollars, we need to budget our time.

April had to unlearn the false narrative playing in her head: that her personal deficiencies and lack of effort (as opposed to her lack of a schedule) were the causes of her degrading performance and growing anxiety. To help April, I asked her to start by showing me her daily schedule. Sheepishly, she opened the calendar app on her phone and let me scroll through her week. I saw mostly open days with a few scattered engagements. It was clear by glancing over her schedule that April was leaving her time up for grabs.

Her day was full of tasks other people wanted her to do, when they wanted her to do them. For example, if a new hire wanted to schedule time to “pick her brain” (a gross term we should really stop using), she’d give him access to her calendar. Of course, he would select a time that was convenient for him. Similarly, April prided herself on having an “open door” policy. Anyone who had the smallest question could walk in and interrupt her at any time. And if a client needed to talk about something, day or night, she was always answering the call.

Early in April’s career, always being available was a great strategy. Back then, her only responsibility was selling. And sell she did. Her entire day was scheduled for doing just one thing well. As the years passed and April got better at her job, her company gave her more clients and more responsibilities. As a result, her old methods stopped working. Additionally, her aspirations had changed; she wanted a senior management promotion and to lead a team. However, the way she worked hadn’t changed. That’s how April found herself in a crippling rut: She wasn’t evolving her ways to match the changing conditions of her interests and job demands. If she was going to advance in her career, she’d have to upgrade her skills and start managing her schedule instead of letting it manage her.

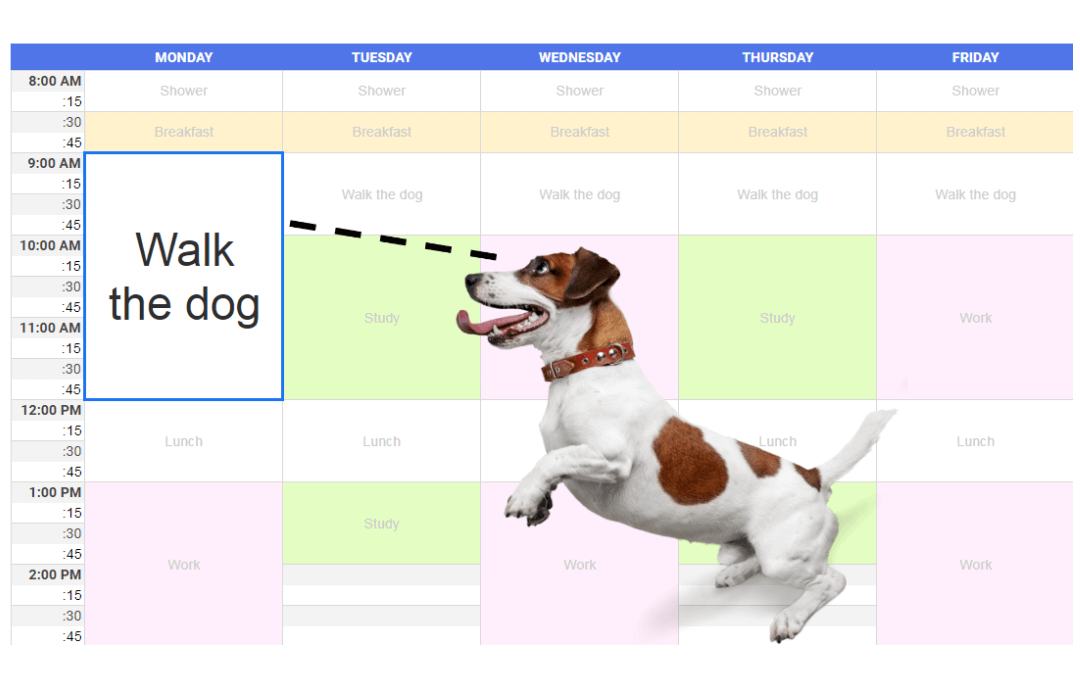

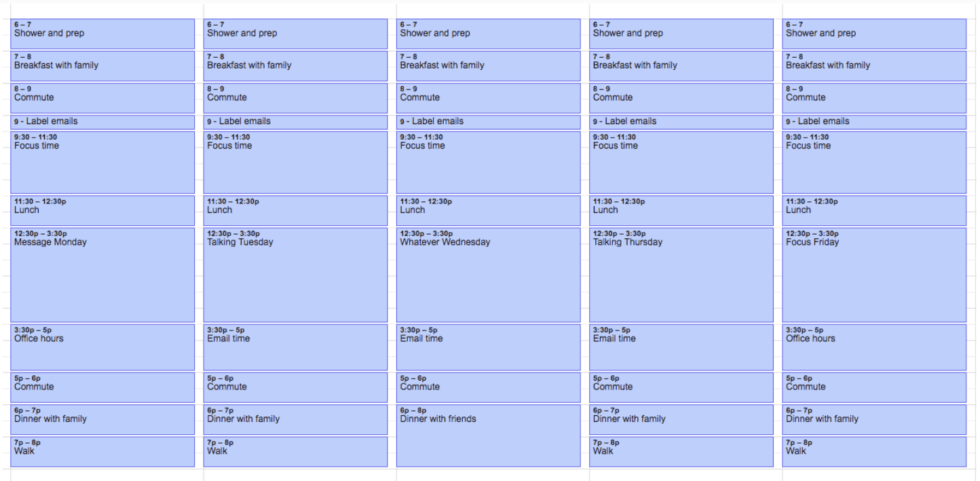

After she decided how much time she’d spend on each domain in her life, I advised April to set a weekly schedule template. A template that shows a hypothetical, perfect week consistent with her values. I asked her to use a schedule maker and leave no open spaces during her waking hours. She was holding a place for everything important to her in properly allocated time slots on her calendar. Now April could ensure the most vital things never fell through the cracks.

She started this process by opening up the schedule maker and prioritizing and planning her “you” time, the self-care time she needed. I asked her to think critically about how much time she needed for sleep, basic hygiene, exercise and anything else she found essential for her well-being. For April, that also included time for watching television and reading books. Then, I asked her to fill in her day with her next top priority after taking care of herself. She booked time in her weekly schedule template when she wanted to spend time with her husband and kids. Nightly dinners and weekend mornings were critical to her. She also found a sliver of time every week for friends and calling her parents. Then, she layered in time for work.

Scheduling her time this deliberately didn’t come naturally to April. But she endured the discomfort of learning a new skill and, as a result, loved the outcome. She now had a view on her entire week down to the minute that respected her values and reduced distractions. It ultimately granted her more time to do what she really wanted.

Now that April had her calendar painted in broad strokes according to the three domains of her life, it was time to dig deeper into her working time, which, despite prioritizing the other two areas of her life first, still represented the largest amount of time in her schedule. April subdivided her workday into the most important tasks she wanted to be sure to do daily. She carved out time for focused work first. From her experience, she knew creating new client proposals could be done faster and better if she did nothing but that task, without interruption.

Every diversion slowed her down and made it more difficult to get back to customizing the pitch. Then she reserved a large chunk of time for client calls and meetings, then time in the late afternoon for processing emails.

It was a rough sketch she knew wasn’t set in stone. Nonetheless, she now had a valuable asset preventing her from slipping back into old habits. No more Maverick-style over-commitments that would limit her productivity and strain her sanity.

An example of a “timeboxed” schedule planner

3. Sync with Stakeholders

By using a schedule maker to build her weekly schedule template, April now had a clear plan she could discuss with the people who placed the largest demands on her time. First, she met with her husband to review her weekly plan. Together, they made some small tweaks and made time for a weekly fifteen-minute schedule calendar sync immediately after lunch every Saturday. During that time, they’d look over each other’s plan for the week and made sure they had enough time scheduled for managing their household and spending time together as a family. April was thrilled.

By using a schedule maker to build her weekly schedule template, April now had a clear plan she could discuss with the people who placed the largest demands on her time. First, she met with her husband to review her weekly plan. Together, they made some small tweaks and made time for a weekly fifteen-minute schedule calendar sync immediately after lunch every Saturday. During that time, they’d look over each other’s plan for the week and made sure they had enough time scheduled for managing their household and spending time together as a family. April was thrilled.

Then it was time to discuss her schedule with her boss David. To her surprise, when April sat down with him she found he was extremely supportive about her intention to stick to a more planned-out day. “He knew I was burning the candle at both ends,” she told me. “When I proposed a weekly schedule, he actually seemed relieved. He told me it was helpful to know when he could call or message me instead of guessing if I was with my family.”

When she sat down with David, she made a surprising discovery. Many of the commitments clogging her calendar that she believed he cared about weren’t nearly as important to him. He preferred her spending time closing more deals. David also agreed she didn’t need to attend so many meetings or mentor so many people. Better still, less meetings and mentorships weren’t going to hurt her career ambitions. She could still be on track for promotion as long as she put in the time for her most important task: selling!

To stay in sync over time, April and David decided to meet for fifteen minutes every Monday morning at eleven o’clock. The time spent looking at her schedule for the week ahead would give them both peace of mind. It allowed them to make sure that April was spending her time well, and if not, would allow them to go back to the schedule maker and adjust accordingly.

At the end of our meeting, April realized another benefit. She could now not only gain greater control over her day but also cut back on time tethered to her phone at night. This time came usually at the expense of her personal life. Staying synced at work with her boss, therefore, fostered a virtuous cycle that benefited both her home life and work life.

As long as she stayed the course and conducted her weekly calendar reviews with David, she could achieve her biggest goals.

Finally, I asked April to book a weekly fifteen-minute schedule sync with herself. I told her it was critical to open her schedule maker, review her weekly template and make adjustments. Once she had a template in place, it took only a few minutes to reflect, refine, and revise her schedule for the week ahead.

The goal of using a schedule maker isn’t committing to a perfectly strict plan. Instead, the idea is to use the schedule maker to set up a routine to improve your schedule over time. The point is to have a weekly schedule template that serves as a default to return to and make slight revisions week after week. It allows you to get better at understanding how long tasks take and making sure you make time for actions that reflect your values.

Your Weekly Schedule Is Done! What’s Next?

Using a schedule maker helps you answer the fundamental question of what to do next. A quick glance at your calendar made in advance and with intent tells you exactly what you need to do. It reminds you that anything not on the plan is a distraction.

You too can take control over your life. Stick to a practice of keeping a schedule consistent with your values. Make a template and sync-up regularly with yourself and the stakeholders in your life. If you do, you will find time for doing what you intend to do rather than getting distracted.

As for April? She recently got her promotion to a management role and I couldn’t be happier for her.

If you found this guide on using a schedule maker helpful, I hope you’ll share it with others. Perhaps you’d like to introduce the idea of syncing your schedules to your significant other, work colleagues, or boss? If you’d like more science-backed insights for living your best life, check out my other articles below.

Free Schedule Maker Template

Take back control of your time and design your ideal day.

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Related Articles

- Unlock Your Potential With The Power Of Belief

- The Pain Paradox: How Fear of Pain Creates More Pain

- Let’s Not Decide Who Kids Are Before They Do

- How to Find Fulfillment When Your Job Doesn’t Provide It

- Why Seeking Approval is Killing your Potential

- How Successful People Timebox

- Stop Gaslighting Yourself: Why Your Memory Isn’t as Reliable as You Think

- How to Protect Your Focus Without Burning Bridges

- The Real Culprit Behind Plummeting Children’s Mental Health

- The 4 Secrets to Storytelling for Business